My initial response to The Austen Project was the mental equivalent of a head-shake and an eye roll.

WHY spend time rewriting the classics? Surely the whole point of a classic is that they are, in some ways at least, still relevant in contemporary society and culture? If a book is no longer relevant to its readers then can it really be considered a classic?

The idea that such projects are a homage to the original author I find disquieting. Surely the best way to honour an author is to read them, enjoy them or write about them, not try to one-better them by making their novel “up-to-date” or “accessible”. Besides, isn’t this kind of, frankly, tampering with the originals an insult to modern readers? Are we considered too lazy to read a book labelled “classic”? Are we perceived by publishers as too dense to understand narratives teeming with subtle irony and satirical flourishes? Or too lacking in empathy to read about people dancing at balls instead of getting drunk at parties?

And yet… I largely enjoyed reading ‘Pride and Prejudice with Zombies’, though the conceit had worn thin by the end. I relished Andrew Davies’ five hour long TV adaptation of ‘Pride and Prejudice’, which captured Lydia’s exuberance and Jane’s sensible nature perfectly. Sightly more recently, I thoroughly enjoyed Gemma Arterton’s adventures in ‘Lost in Austen’, a fabulous TV mini-series in which P&P obsessive fan Amanda accidentally enters Elizabeth Bennet’s world and immediately begins messing up the storyline. (Who wouldn’t love a re-working that includes a gay Caroline Bingley and a secretly honourable Wickham?) And just in case that isn’t enough P&P variants, top of my Christmas list this year is a copy of Jo Baker’s ‘Longbourn’, which follows the servants’ perspectives on the Bennet family.

Amanda accidentally enters the world of ‘Pride and Prejudice’ – and makes some surprising discoveries.

What all these have in common, though, is that, like ‘Bridget Jones’ Diary’ or ‘Clueless’, they are adaptations or revisionings of Austen’s work, not simply rewritings. What’s the difference? To my mind, a revisioning is doing something new with Austen’s original storyline; a rewriting is simply updating the language and turning carriages into cars, butlers into bouncers and dances into discos.

Perhaps this is mere quibbling over terminology, which other people may interpret differently. And, of course, revisionings are not always well-done. (P.D. James’ ‘Death Comes to Pemberley’ is an interesting premise but is, arguably, executed without sufficient attention to either the nature of Austen’s characters or the conventions of the crime genre.) But what benefits would a straightforward rewrite have? Actually, more than might at first appear.

Although some of the more recent Austen book covers present her works as romantic chick-lit, Austen has traditionally been seen and indeed saw herself as a social commentator and satirist. We all know that her social commentary can slip by readers who are unfamiliar with, for instance, the various types of carriage her characters use and their significance, or how many servants indicate that one is truly upper-upper-middle class, or how Bath was viewed in the 1780s by Londoners, which includes, well, almost everyone really. Could a rewriting that introduced Robin Reliants and Jaguars help us all to grasp the finer points of Austen’s social commentary? Of course, many editions come with helpful – or even not so helpful – notes that explain various historical points to the keen or student reader in a well-intentioned desire to illuminate the meaning of the text. Yet how far the typical reader can enjoy Austen’s intended humour when reliant on references that may themselves be a little obscure is still a pertinent question. Perhaps a straighforward rewriting would even help A-level students to understand the nuances of Austen’s works better?

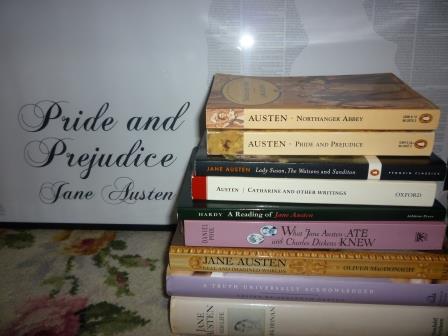

A selection of my Austen-related book collection…in front of my A0 sized full-text poster of ‘Pride and Prejudice’. Obsessive? Me?

Sadly, rewriting does not always clarify the original text for readers. I will never forget watching Baz Luhrmann’s ‘Romeo + Juliet’ with a year 10 class. After watching the Montagues and Capulets bicker at a petrol station, one of my students looked carefully at his copy of the text, at the screen, at his text. He put up his hand. “Miss…in Shakespeare’s one…were they filling up their horses?” He was genuinely trying to use Luhrmann’s film to inform his understanding of Shakespeare’s text, just not in a particularly helpful way. Not everything can be simply “translated” into modern English and inevitably, in rewriting texts, even if you keep much of the dialogue and action, you create new meanings.

Austen herself clearly thought that readers being able to interpret small details was important. When ‘Northanger Abbey’ was first published it was prefaced by a note from the author, stating that: ‘The public are entreated to bear in mind that thirteen years have passed since it was finished, many more since it was begun, and that during that period, places, manners, books, and opinions have undergone considerable changes.’ If thirteen and a bit years had rendered Austen’s meanings less clear or her irony less appropriate, how can modern readers be expected to cope?

And yet…it is impossible, when reading ‘Emma’, not to shake our heads and groan at Emma’s folly and blindness in her match-making; impossible, when reading ‘Pride and Prejudice’, not to shudder at Mr Collins’ rude address to Elizabeth and his pompous assurance that she may not receive another proposal; impossible, when reading ‘Northanger Abbey’, not to feel the full weight of Catherine’s ignorance as she transforms Isabella into a devoted sweetheart and the General into a murderer. There are many other impossibilities. In short, the heart of these stories and the hearts of their characters are still beautifully illuminated for even the most modern reader. This is (partly) why the stories are classics and Austen so revered. Surely, we should let them speak for themselves?

More of my thoughts on The Austen Project can be found below:

The Austen Project – links

- The Austen Project 1

- ‘Sense and Sensibility’ by Joanna Trollope

- ‘Northanger Abbey’ by Val McDermid

- ‘Emma’ by Alexander McCall Smith