I had never heard of this book until it was selected as a book group read.

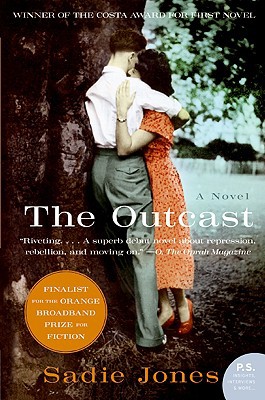

The plaudits on the back cover suggested it was written in a similar style to ‘Atonement’ so, having loved that book, I was keen to read this.

The premise

Under the neat façade of the church-going, lunch-attending 1950s middle classes, rural life is full of familial abuse and misery. Lewis Aldridge, returning from jail at the tender age of nineteen, is frustrated by the polite hypocrisies of this world. A social outcast who is convinced he is broken, his actions quickly grow wild. Kit Carmichael, four years younger, has always adored Lewis. However, in her desire to help him, she will expose other secrets to public view…

The opening

After a prologue describing Lewis’ difficult return from prison, the narrative joins Lewis at age seven when his father is demobbed. This is a critical point in Lewis’ life and for years afterwards he defines his life into two sections: before and after his father returned home. Gilbert brings a ‘stuffiness’ with him that Lewis and his mother resist, but tragedy soon divides Lewis’ life into another before-and-after.

The prologue sets the style for the whole novel: thoughtful, painful, somehow separate. What could be simply a clumsy cliffhanger – why was Lewis in prison? Is he dangerous? – is actually an effective introduction to Lewis’ psyche. Given the events of this chapter and the length of time Lewis was in jail I felt that it was fairly easy to guess what he had done anyway, so it doesn’t create intense suspense. Instead, the focus is on how uneasy Lewis feels about his place in this world.

My thoughts

I found the premise of the novel interesting, although it is certainly not a book I would have selected myself, mostly because I’m so busy trying to keep up with the work of authors I already know I like! This isn’t a new topic (secretly abusive middle class families) but it is handled very well in this book.

I found the 1950’s setting was neatly evoked through small details and was convincing without the need for layers of description. In fact, Jones uses description sparingly throughout: it is always purposeful, which I liked, and gives the narrative coherence rather than being a diversion.

This is Jones’ first novel but she has been a screenwriter for fifteen years and this novel has clearly benefitted from her background: it ‘flows’ cleanly from beginning to end. Characters are swiftly delineated, minor details gain significance, and the reader experiences the point of view of several characters, including Lewis, Kit and some rather less sympathetic figures. These changes are managed very smoothly and the actual reading experience is very easy.

Screen shot from the film of Jones’ book…which was originally conceived as a screenplay.

When the tragedy occurred early on, I found Lewis’ responses utterly convincing. This worked well to create a bond between the reader and the character which allowed me to develop sympathy for Lewis that sustained my involvement in the rest of the novel. For a book like this to work you have to care deeply about the central protagonist. Fortunately, Jones has handled the narrative in such a way that it is impossible not to feel for Lewis.

This does mean that his father, Gilbert, comes across at points as being almost inhuman in his harshness and some critics have suggested that Jones misses a trick by failing to explain his cold behaviour. I would argue that his behaviour is adequately explained by the era and his time spent at war. Besides which, developing more sympathy for Gilbert would surely have reduced feeling for Alice (his new, young wife) and Lewis.

Perhaps a more significant problem is the portrayal of Dicky Carmichael (Kit’s father), who also lacks an explicit justification for his rather more brutal approach. However, he is essentially a bully who is enabled by the social mores of the period. Once again, this lack of development of his character means that we view him from Kit’s perspective and it enhances our sympathy for her and our sense of horror at the hypocrisy in this society. I do not see these omissions as flaws in Jones’ writing; rather I think they are sensible decisions which focus a reader’s sympathy on the children, who gradually become a symbol of hope.

Both fathers become more distasteful as the novel develops and their strictures (Gilbert) and behaviour (Dicky) become more explicitly dictatorial and abusive. Jones’ gradual development of their characters means that neither becomes simply a caricature and their actions are shocking without shaking the reader out of the world Jones has created.

A warning

Without wishing to reveal too much of the plot, I feel readers should be warned that a self-harm theme develops in this book. While scenes depicting harm are not gratuitous, they may well make some readers feel very uncomfortable. Personally, I did find these scenes quite difficult to read and I had to put the book down and leave it for a few minutes sometimes before continuing. Obviously this will not affect all readers, but I felt that some might appreciate being made aware of this aspect of the book.

Conclusions

This is easy to read in the sense that the narrative flows very smoothly. It can be quite difficult to read in the sense that the protagonist is in a lot of emotional pain throughout much of the book. I found this to be a quietly compelling read with a suitable ending. (I would have quite liked an epilogue, but the ending is fitting and could be viewed as powerful / rather melodramatic.) The main characters are very sympathetic (but, crucially, not spineless) and you really care about how their lives will develop. The claustrophobia of village life is effectively evoked, as is the enormous power our families have over us.

Definitely worth reading and I will be on the lookout for ‘Small Wars’, Jones’ second novel.

‘The Outcast’,

Sadie Jones,

2008, Vintage, paperback