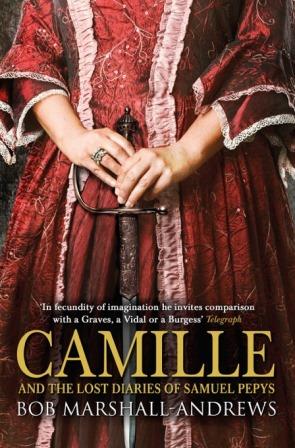

Samuel Pepys is one of England’s most famous diarists.

Those who know much about him might know that he wrote ten years of diary entries (from 1660-’69) until his eyesight became too poor to continue. He contemplated getting someone else to write for him, but never did. ‘Camille’ explores what might have happened if he did, and if the amanuensis in question was a French woman willing to assist with scandalous political negotiations in her native country.

What’s going on?

It’s 1670 and Charles II is troubled. Parliament won’t give him as much money as he desires and he wants to get rid of them – but how? Louis XIV might be willing to help him out, if Charles will join him in a(nother) war against the Dutch, but Louis must be satisfied with the strength of England’s navy. Samuel Pepys is summoned by Charles and instructed to travel to France to negotiate for him. Pepys is willing enough, but can’t speak French with the depth he might need for such delicate discussions. Can he persuade his new companion and scribe, Camille, to travel with him to assist?

Camille is a talented actress and a beautiful woman who has fled France after an incident in Paris left her life in danger from one of France’s most powerful families. If she travels back to France she will be risking her life, but when fresh news from home reaches her she is resolute: she will return to Paris to seek her revenge, even if she dies in the attempt…

What’s it like?

Dramatic. Frustrating. Humorous.

From the opening words – ‘It is an awesome thing to kill an admirer’ – Marshall-Andrews creates a world seething will drama and intrigue. We witness Camille’s actions, including her calm escape, and realise our narrator is an extremely capable young woman (who has been pretending to be a man…) She is instantly likeable, too. Her reluctant but admitted pleasure in the compliment given by the man she subsequently slayed makes her an utterly convincing young lady.

‘It is an awesome thing to kill an admirer’

This is useful, as we can forgive her when she appears blind to the completely logical conclusion of her actions. We are waiting for the information Camille finally receives long before she is blindsided by it.

There’s a lot of set-up initially to establish Pepys and his role in particular, but it’s cleverly done and the second of many occasions where Camille is able to take advantage of other characters misconceptions about her. There’s much bawdy humour as her body is lewdly complimented, with her fellow travellers unaware that she can understand every word they say.

Who did Pepys write for?

My frustration arose in relation to the presentation of Pepys’ interactions with his diary. As any scholar with the most basic interest in Pepys will know, his diaries are so valuable because they offer an uncensored insight into life in 17th century England. Pepys wrote for himself, in shorthand and sometimes in code, about the most basic, private, dull aspects of his existence as well as the momentous events of the day. His honesty about his health and his relationship with his wife makes him a trusted authority on matters of the day for historians.

‘These diaries, Catherine, are for posterity.’

Marshall-Andrews presents the diary instead as a knowing monument to posterity; Pepys selects paper that will last hundreds of years and tell Camille: ‘Perhaps in hundreds of years’ time, clever people will spend their lives examining what I say, unravelling codes and the like’. Then, later, more bluntly: ‘These diaries, Catherine, are for posterity.’ Moreover, Pepys repeatedly leaves out unflattering details about his adventures, leaving Camille to lecture him on accurate reporting and representation.

Amusing, yes, but inaccurate and perhaps mildly frustrating for anyone with a genuine interest in Pepys’ diaries…and surely that’s anticipated to be a large chunk of Marshall-Andrews potential audience? The author stated in an interview for BBC London Radio that anyone reading the diaries will find them to feel unfinished and will want to know what happened next. I can certainly see why, as Pepys lived a good number of years subsequent to his decision to stop writing, and Marshall-Andrews’ fiction does fill in some of those gaps, but I would still have preferred Pepys to be less concerned with posterity.

Final thoughts

This is an interesting alternative history that gives Samuel Pepys responsibility for negotiating an important secret history. It’s fun to meet King Charles and King Louis, and to watch Camille play the spy (and the seductress!).

Given her focus on physical beauty, I wasn’t convinced by Camille’s supposed inexplicable attraction to Pepys, or the ‘literary love story’ promised by the blurb, but it was amusing to see Pepys dictating his thoughts about her into his diary and seeing how she responded. The ending may divide readers; is it beautifully romantic or strikingly convenient?

Overall, ‘Camille’ is a light and entertaining read, especially if you’re interested in this period of history and / or political machinations.