Miserable winter weather always leads me to crank up the heating, feel guilty about it and read a book about sustainable living.

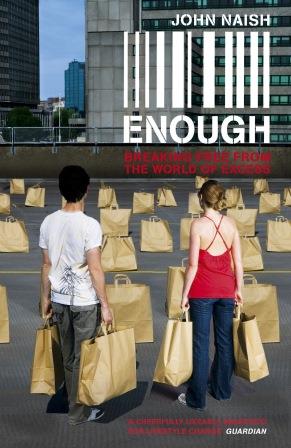

Recently I re-read ‘Enough’, which could be described as a critique of our cluttered lifestyles from an evolutionary psychologist perspective.

What’s it about?

John Naish, lifestyle writer for The Times, argues that over human evolution our desire for ‘more’ has resulted in our reaching quite a pleasant stage in our development. Now, we no longer need to chase unthinkingly after more, but our brain doesn’t know this and keeps trying to follow our inbuilt urges. This is leading to mass unhappiness, stress and the destruction of Earth.

However, Naish stresses that this is not a self help book or a save the planet guide, but an almost philosophical meditation on where we are going wrong, why and what we might do to stop the merry go round. I was particularly interested by his suggestion that we should promote contentment over the lure of Happiness (especially after recently reading this article about how the pursuit on happiness can lead to, er, unhappiness).

What’s it like?

Naish’s style throughout is colloquial, easy to understand and immediately engaging. In the book’s opening paragraphs he envisions aliens orbiting the Earth, shaking their heads sadly at the ruined planet and saying to each other, sympathetically but resignedly, “daft buggers”.

Naish explains why choice is not simply an illusion, but actually something rather more toxic.

Each chapter examines a different area of life, such as food, and uses our past as tribal brings to explain what does appear to be distinctly tribal behaviour. For each subject, Naish explains why choice is not simply an illusion, but actually something rather more toxic. Along the way he covers topics as diverse as the growing trend for buying designer vaginas, Britain’s poor take up of holiday entitlement and the increasingly overwhelming options available to consumers when buying a gadget. Chapters aren’t comprehensive – surprisingly, the chapter on information ignores social media entirely.

References abound but aren’t indicated in the body of the text, which is a shame, as if you are interested in finding out where a particularly startling claim has come from, you have to just turn to the back of the book and see if there is an explanatory note. Most statements are supported by references and it was clear that, despite the informal tone of the book, Naish’s apparently meandering thoughts are based on solid research. Many of the findings from these studies are fascinating. (Did you know, for example, that regular communal singing appears to enhance wellbeing to the extent that lifespan is increased?)

This is is an important book which successfully examines our modern lifestyle without preaching.

However, not all references are equally weighty. Many “scientific” references were from broadsheet newspapers, which I learned to distrust after reading Ben Goldacre’s “Bad Science”. I thought it was a shame Naish hadn’t referenced the source of the claim as well as the relevant newspaper article. Of course, most popular science stories in the paper don’t refer to the specific piece of research (often because they are wilfully misrepresenting it in their desire to excite newspaper readers with a random titbit of “fascinating” “discovery”) but it seems to me that there is no excuse for relying solely upon the journalist’s interpretation of the work. Either Naish has looked at the original source, in which case he could easily share that with his readers, or he hasn’t and is relying upon potentially exaggerated and / or distorted reports. I felt this was disappointing.

Critics of evolutionary psychology are likely to disagree with a lot of what Naish says but I felt that much of it rang an uncomfortable truth somewhere in my mind. For instance, I find it hard to listen to the rational part of my mind when shopping. (The rational part of me knows I already have too many T-shirts to fit them all in my dresser at once, but somehow I still buy that beautiful top as a “one off”.) This strengthened the appeal of the book for me as there was a definite sense of experiential truth.

Final thoughts

I liked the attitude Naish adopts throughout. There is a sense of rueful “what could you expect based on our past?” which is neatly balanced with a sense of what needs to be done to achieve real contentment: being ‘eco’ needs to become hip – permanently. However, much as I understood how this conclusion was reached, Naish lacked a plan to achieve this, which I felt was a shortcoming. Furthermore, the attitudes he wishes to take advantage of to achieve this transmogrification of the world’s society are exactly the snobbish attitudes he admits we should ultimately be striving to eradicate. Hmm.

That aside, this is is an important book which successfully examines our modern lifestyle without preaching. It is alternately inspiring (the dairy farmer who refused to become a businessman), chilling (if we survive the next twenty years without the end of the world as we know it, we won’t survive the next twenty), and depressing (how can these much needed seismic shifts in attitude occur?)

Highly recommended.