There are certain facts almost everyone remembers from school.

- Christopher Columbus discovered America in 1492. (Or did he?)

- The Dark Ages were a period of intellectual, well, darkness. (But were they?)

- The Magna Carta was a revolutionary document that forms the basis of our modern democracy. (So why did Oliver Cromwell call it ‘Magna Farta’?)

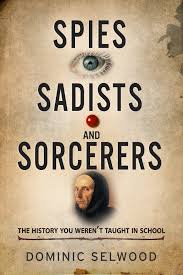

Unfortunately, if historian Dominic Selwood is to be believed, it turns out that what we were taught was inaccurate, to say the least, and our memories are of carefully crafted myths, NOT facts.

What’s it about?

See above. Selwood aims to disentangle fact from fiction and ensure readers are equipped with the information behind the myths. He states that ‘Many of the stories in this book are about setting the record straight. Or, at least, presenting another perspective.’ The facts of history are usually undisputed, but the interpretation of them is another matter, and once a particular interpretation of events becomes dominant, it may not be challenged, regardless of its potential inaccuracies.

The book is organised into sections covering:

- The Ancient World,

- The Mediaeval World,

- The Renaissance and Reformation,

- The Victorian World,

- World War One,

- World War Two,

- and The Modern World.

Within each section readers will find at least two articles debunking standard historical perspectives and illuminating a more modern understanding – often a darker one.

What’s it like?

Often interesting, occasionally horrifying, usually well organised. Obviously with such a plethora of topics, it is unlikely readers will be fascinated with every historical wrong Selwood deigns to right, and it seems likely that the more ‘popular’ topics will be better thumbed, but his written style is accessible and clear, if a little repetitive at points.

For me, the most affecting chapters were those on Christopher Columbus and the so-called ‘Dark Ages’.

It was horrifying to read about the way Columbus, his ‘teams’ and subsequent generations of transplanted Americans have systematically destroyed the Indians. This is a topic I have read about before, but in a fictional form, and it was shocking to be given the words of several American Presidents, not just authorising or condoning, but actually making a virtue out of, a sequence of acts which, Selwood argues, was actually genocide.

Should we really celebrate land grabs and the annihilation of a people?

In its own way, it was equally shocking to read about Henry VIII’s destruction of 1,000 years of English art in order to change an unwilling population’s religion. Selwood notes that ‘The Tate recently estimated that over 90 per cent of all English art was trashed in the period’ and that the ‘Bodleian, for instance, was left without a single book‘ (my italics). No wonder the ‘dark ages’ appear dark from a modern perspective – or at least, from a UK modern perspective, since, as Selwood notes, ‘The United Kingdom is the only European country to use that phrase’.

It’s difficult to admire an age’s culture once it’s been systematically destroyed.

More editing would have been useful. These articles originally appeared in The Telegraph and The Spectator, ‘designed to give historical context to contemporary events or anniversaries’, and it appears that the only changes Selwood have made are to tweak some of the titles slightly and add brief introductions giving the context of each piece. This is useful, of course, but the essays themselves would have also benefitted from a touch of judicious editing. Usually the repetition of information is sufficiently minor and infrequent to pass unnoticed, or at least without comment, but the two articles about the Elgin Marbles are nearly identical and could usefully have been edited to create one single article.

Final thoughts

This is an interesting collection of essays exploring a range of topics which Selwood consistently links to modern events and attitudes (there’s a whole chapter comparing Cromwell to ISIS). He seems hopeful that we might learn valuable lessons from history with more accurate knowledge…but the very history he explores shows that we tend to make the same mistakes.

This book is great for readers like myself, with a mild interest in history and a patchy knowledge of historical events; whether it would hold the interest of more knowledgeable readers I’m less sure, since the key interest is in the ‘twists’: the things we’ve never learned. For instance, I studied the ‘modern’ Israeli / Arab conflict at school, but don’t recollect ever being made aware of the full, torturous history surrounding Jerusalem – though it’s entirely possible I’ve just forgotten. (Greater understanding of the historical roots makes me feel it will never be resolved, but that’s a whole separate discussion!)

In short this was an enjoyable and often fascinating read which certainly left me feeling like I understand more about key historical events.