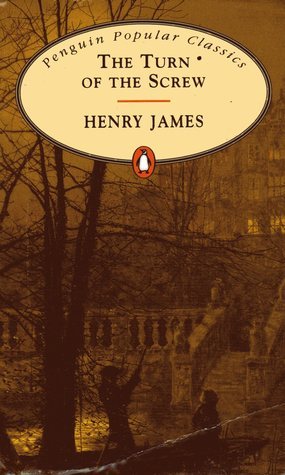

What’s more entertaining than a ghost story in which a child sees a ghost?

A ghost story in which two children see two ghosts. Obviously. Such is the conclusion reached by the eager aristocratic circle of guests who sit sharing ghost stories at the opening of Henry James’ gothic novella, who are desperate to hear one particular guest, Douglas, recount the tale spun by a late governess he once knew.

‘The Turn of the Screw’ is a classic ghost story, with good reason, though there’s far more to this narrative than the simple shock of a haunting, even a haunting that appears first to two innocents.

What’s it about?

A new governess is in sole charge of two orphan children. She grows increasingly uneasy as she begins to see and hear strange things. As she is drawn into a frightening battle against unspeakable evil, she decides to take action, with terrible consequences…

What’s it like?

‘The Turn of the Screw’ is determinedly ambiguous, with few actual events, plenty of gaps in the narrative, and a final, shocking, ending.

Surprisingly little actually happens – or perhaps I mean that surprisingly little definitely happens. Can the children really see the ghosts of their former, recently deceased, governess and valet? Or is our unnamed narrator imagining both the ghosts and the children’s response to them?

As the story progresses, the unanswered questions mount up. What, exactly, did delightful Miles do at school that led them to expel him? What did the late servants die of, and what was the exact nature of their relationship with the children? What did little Flora say to Mrs Grose that frightened her so much? Be prepared to stay resolutely in the dark!

James’ written style

Like many late nineteenth and early twentieth century authors, James is fond of using long, complex sentences to convey carefully moderated impressions. The first sentence is sufficiently indicative of James’ style:

‘The story had held us, round the fire, sufficiently breathless, but except for the obvious remark that it was gruesome, as, on Christmas eve in an old house, a strange tale should essentially be, I remember no comment uttered till somebody happened to say that it was the only case he had met in which such a visitation had fallen on a child.’

Long doesn’t have to mean complicated, but it’s true that most of James’ sentences pay careful rereading; if you skim the nuances will be lost, and James is all about nuance: it’s why this story can be interpreted in dozens of, frequently contradictory, ways.

Final thoughts

James repeatedly prevents us from reaching a firm conclusion, even at the shocking (and rather abrupt) conclusion. Ambiguity can irritate me, but this inability to know is so firmly and skilfully threaded through the whole story that I found it fascinating and have been reading criticism of the book on and off since I finished it over a week ago.

This can be enjoyed as a simple ghost story, but it’s pretty much impossible to read without wondering if the inexperienced young governess is simply losing her mind. Her effusions over the children are erratic and the final sentences of the novella deeply chilling.

I had no fond memories of studying Henry James, but since reading this I am certainly tempted to try another of his ghost stories.