There are many times when I’d love to know what my son is thinking.

What is he thinking when he completely ignores me repeatedly calling his name? (Has he heard me or is he too absorbed in his play?) What about when he says, “Mummy…” then falls silent for a full minute, before repeating the process several more times? (Is he gathering his thoughts? Did he forget what he meant to say? Is something bothering him? Or is it a verbal tic, mere oral filler?) When he tells me, yet again, that the best part of his day was playing by himself, with his toys, does he mean that? (Has he actually remembered what we did today or just given an easy, default response? Did he really not enjoy the family outing / visit to friends / exciting trip as much as he enjoyed lining up all his buses on his playmat again?)

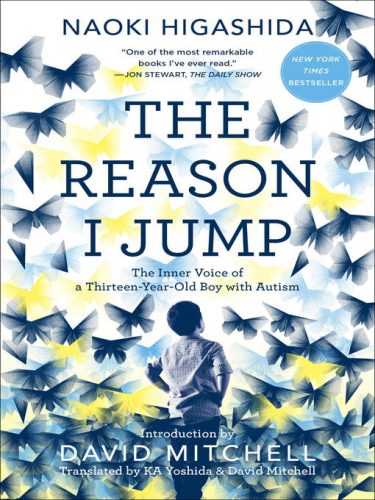

So I was excited to hear about ‘The Reason I Jump’, which purports to be a memoir by a 13 year old boy with autism, explaining some of his autistic traits. Although I found it a very interesting read, I’ve been left feeling a little irritated; I’ll try to explain why.

What’s it about?

‘The Reason I Jump’ is, according to the introduction by one of Higashida’s translators, David Mitchell a collection of, ‘the answers that [Mitchell and his wife] had been waiting for’ about ‘why children with autism do what they do’.

I think this is where the problem arrives. I am genuinely pleased for the translators, who saw a strong resemblance between the degree of autism and the types of experiences recounted by Higashida and those of their own autistic son, which led them to feel that, ‘for the first time, our own son was talking to us about what was happening inside his head, through Naoki’s words’. How marvellous that connection to their own son must have felt. It’s wonderful that reading Higashida’s book ‘allowed [Mitchell] to round a corner in [his] relationship with [his] son’ and I completely agree that knowing your child wants your help can allow you to become a more empathetic parent.

In an FAQ format interspersed with creative writing pieces, Higashida discusses briefly why he or people with autism present with certain common behaviours, including running away, stimming, constantly fidgeting, etc. Most of these are interesting glimpses into an overwhelming world which the person with autism must constantly do battle with and there’s a repeated call for carers and parents to be understanding, which I think is valuable.

What’s it like?

Engaging, disturbing and, increasingly, mystical.

Engaging: Higashida explains that his weird voices, ‘are like our breathing…just coming out of our mouths, unconsciously’ and explains that, rather than being linear as he expects a ‘normal’ person’s memory would be, his consists of ‘a pool of dots’, which makes the right memory hard to find. There are multiple insights like this, which encourage readers to understand just how incredibly hard life is for people with autism. This is genuinely interesting, the reason I chose to read the book, and I can see how it would help carers to reinvigorate their own empathy.

Disturbing: Mitchell concludes in his introduction that Naoki’s book, ‘offers up proof that locked inside the helpless-seeming autistic body is a mind as curious, subtle and complex as yours, as mine, as anyone’s’ and the author himself repeatedly assures us that he ends up ‘feeling miserable and ashamed that I can’t manage a proper human relationship’. The whole book is a portrayal of autism as a form of locked-in syndrome which simultaneously offers a rather twisted kind of hope (there is a ‘normal’ person inside the ‘autistic’ one) alongside what I find a rather crushing sadness (the ‘normal’ person is trapped, in desperate need of your help, and will never fully escape the weight of their disability, though they are keen to try). I think this is actually intended to make readers hopeful, and I’m sure you could read it that way, but I found it desperately sad.

Mystical: I’ve often observed my son’s fascination with water. It’s a common trait in people with autism and I have always vaguely assumed it is sensory in nature – something to do with the rushing sound, or the tickly feeling, or the patterns that form and break so rapidly as the water swirls round and round. Personally, I’ve always found water intensely soothing and calming, so it makes sense to me that other people might feel the same. According to Higashida, however, a person with autism’s obsession with water stems from a rather more meaningful cause:

We just want to go back. To the distant, distant past. To a primeval era, in fact, before human beings even existed. All people with autism feel the same about this one, I reckon. Aquatic life-forms came into being and evolved, but why did they then have to emerge onto dry land, and turn into human beings who chose to lead lives ruled by time? These are real mysteries to me… People with autism have no freedom. The reason is that we are a different kind of human, born with primeval senses. We are outside the normal flow of time, we can’t express ourselves, and our bodies are hurtling us through life. If only we could go back to that distant, watery past–then we’d all be able to live as contentedly and freely as you lot!

I’ll be honest. I’m pretty sure that when my son stares intently at the water whirlpooling down the drain after his bath, he’s working out the physics of the water’s movement and enjoying concentrating on the sight and sound of the experience.

The reason I’m frustrated

Where do I start with the problems that the above (and several similar passages) raise for me?

Most crucially, as the saying goes, if you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism. My brother, my sister and my son have autism and I really wouldn’t claim to be able to speak with confidence about the attitudes, feelings and beliefs of every person diagnosed with autism as a result of knowing them. I understand that Higashida feels able to speak authoritatively because this is how he experiences his reality as an autistic person, and he expresses it beautifully, but I question his right to claim that his experiences are universally felt by all or most other autistic people.

In another chapter he abruptly states: ‘What we just don’t do are disputes, bargaining or criticising others. We’re totally helpless in these scenarios.’ Perhaps for non-verbal people with autism this is the case – my brother is non-verbal and, other than the occasional firm frown and thumbs down sign, usually quite ready to go with the flow – but my son is happy to bargain and my sister is very ready to criticise, so I don’t always recognise the kind of autism the author describes.

Later, Higashida informs us that:

‘I think that people with autism are born outside the regime of civilization. Sure, this is just my own made-up theory, but I think that, as a result of all the killings in the world and the selfish planet-wrecking that humanity has committed, a deep sense of crisis exists. Autism has somehow arisen out of this. Although people with autism look like other people physically, we are in fact very different in many ways. We are more like travelers from the distant, distant past. And if, by our being here, we could help the people of the world remember what truly matters for the Earth, that would give us a quiet pleasure.’

I think that mystical passages like these distracted me from what I felt was the core of the book – the explanations about why children with autism act as they do – and left me with quite a negative feeling, even though I actually found most of the book fascinating and have already found myself re-reading most of the FAQs.

Cause for concern?

I notice there have been some concerns raised about the validity of this as Higashida’s own words, due to the non-vocal communication method he used to write the book and the suggestion that some of the sentiments raised seem to reflect more what one might expect a parent carer to hope for than a 13 year old boy to feel. It feels relevant to mention that Anne Frank was 13 when she wrote her diary; being 13 is not, in itself, a barrier to writing sensitively or effectively or about challenging topics.

It is true that Higashida is considered non-verbal and that one common trait displayed by people with autism is a very literal understanding that precludes them using or understanding metaphors and similar imagery. It is also true that autism is a spectrum and that each individual varies in terms of which traits they display and to what degree. Although attempts are regularly made to refine the broad descriptor ‘autism’ in terms of severity / the ability of the individual to function, ‘autism’ is a slippery disability and considering anyone too ‘severely autistic’ to be able to achieve a certain aim at any time is being too simplistic. In short, I see no real reason to believe this isn’t Higashida’s own work or his own experiences, but I do not consider this proof that every autistic person is essentially suffering from a kind of locked-in syndrome.

Final thoughts

I thought David Mitchell’s introduction was brilliant and should be required reading for, well, everyone, but especially teachers and carers for people with autism. The chaos inside an autistic person’s brain and body he invokes is frightening and demands a response from observers that seeks to actually understand and support the person, rather than simply trying to stop them demonstrating instinctual behaviours.

Higashida’s insights are even more intriguing and worthwhile, but as the book continued I became increasingly frustrated by his use of ‘our’ and ‘your’ to carve out two separable – and knowable – experiences. The person with autism feels this way. You, the carer, won’t understand because you find this situation easy. Somewhere in this dichotomy, despite all the author’s insistence on empathy and understanding, it feels to me that he’s forgotten what an incredibly broad spectrum of needs and achievements can be found within both neurotypical individuals and those with autism.

Despite this, and my reservations expressed earlier, I do think this is a very worthwhile read for anyone wanting to understand more about the experiences of young people on the autistic spectrum. Naoki Higashida has achieved something quite amazing and it has encouraged me to believe that my own son, with the right support, can achieve his goals in time.

‘The Reason I Jump’,

Naoki Higashida, translated by KA Yoshida & David Mitchell,

2014, Sceptre, paperback