Lily was dead. To begin with.

Of course, Lily doesn’t realise she’s dead until the police arrive and completely ignore her, focusing instead on something behind her, which turns out to be her dead body. And it’s definitely dead:

‘I said, I’m not sure you’re going to need the defibrillator, Gary…Because her f***ing head is on backwards’. Lily has to admit this is true, though when the paramedics declare ‘Life extinct’ she shouts with irritation that she’s ‘not a dinosaur.’ Unfortunately, they can’t hear her, and nor can anyone else. Having watched the police and paramedics process her body, Lily climbs with it into a van, ready to go ‘wherever dead people are taken’. But Lily’s not ready to die yet…

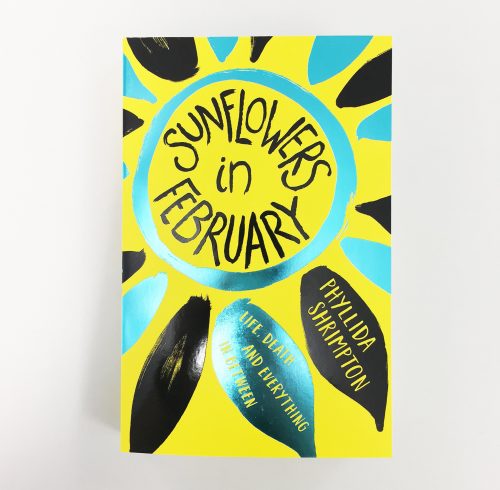

What’s it about?

Lily doesn’t know what to do now she’s dead. To begin with, she observes: her own body in the morgue; her own funeral; her family disintegrating in their grief. But then she seizes a surprising opportunity – could she have another life after all? After all, Lily is only 15. She’s got a lot of living to do yet.

What’s it like?

Deeply sad but embroidered with deliciously dark humour, ‘Sunflowers in February’ is a sensory celebration of life and living. (After reading this, I am convinced that much of life is simply wasted on the living.)

From the beginning, Lily is clear that she’s not ready to go – go where? go how? – but when she gets an opportunity to stay, it raises a moral dilemma she must face. Lily is a wonderfully real teenager, who reflects that she literally died for the sake of some pretty earrings she’ll never get to wear. Her voice is bold and fearless, sometimes angry, sometimes sad. Of course she’s selfish: she’s 15, and she’ll never be 16. I’m not a believer in any form of afterlife, but it would be quite nice if it did work like this!

Shrimpton writes a lot about Lily trying to come to terms with losing her Lily-ness, some of which is quite funny (though I did feel a little uneasy about the strength of the gender stereotyping in this story), but the real focus of the narrative is Lily’s new appreciation for life. Scents, sounds, hugs – they all mean more to someone who has experienced death depriving them of these things. I loved Lily’s new appreciation for her parents in particular. (My children are still very small but I already anticipate them growing into distant, glowering teenagers, so it’s always a pleasure to read about teenagers who don’t think their parents are completely useless.)

Lily’s refusal to let go of life is sometimes presented as selfish, (well, it is once she’s ‘borrowing’ someone else’s!) but this also allows Lily to perform a redemptive role. I really enjoyed the way Lily ‘does good’ and even though it’s obvious to me why she can’t go, it’s understandable that she can’t see it until much later on, and I loved her bucket list.

Final thoughts

The synopsis could make this sound like a depressing read, but it’s the complete opposite: an uplifting and humorous tale in which death is ultimately accepted and seeds of good come from grief. Lovely.