Would you visit a human safari park?

My guess is that you would be revolted by the terminology, but whether or not you actually visited the ‘park’ would partly depend on how you perceive ancient tribes. Are they human beings – or entertainment for more ‘civilised’ beings? My belief is that you would feel – strongly – that they are human beings with human rights, which should be respected.

But even then, whether you actively respected the autonomy of remote tribes would probably depend to a large degree on whether you felt that it was socially acceptable to treat Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers in the same way Britains once treated the mentally ill patients of Bedlam – as curiosities to observe and seek to interact with. And this perception, inevitably, depends to a significant extent upon how the local government treat the tribes their cultures are adjacent to.

Since 1993, Survival International has been lobbying the Indian government to close the Andaman Trunk Road in the Andaman Islands, believing that only the local tribal people – the Jarawa – should decide if, when and where outsiders traverse their land. In 2002, the Indian Supreme Court ordered the closure of the road, yet it still remains open, allowing tourists to gawp at, take advantage of and spread disease to the indigenous population.

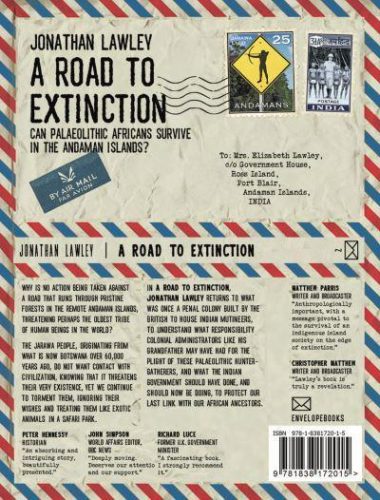

In ‘A Road to Extinction’, Jonathan Lawley, who has personal experience of the tribes from the period of Britain’s colonial rule of Africa, is clear that if the local tribes are to survive, the road must be closed and the tourists banished:

***

Why is no action being taken against a road that runs through pristine forests in the remote Andaman Islands, threatening perhaps the oldest tribe of human beings in the world?

The Jarawa people, originating from what is now Botswana over 60,000 years ago, do not want contact with civilisation, knowing that it threatens their very existence, yet we continue to torment them, ignoring their wishes and treating them like exotic animals in a safari park.

In ‘A Road to Extinction’, Jonathan Lawley returns to what was once a penal colony built by the British to house Indian mutineers, to understand what responsibility colonial administrators like his grandfather may have had for the plight of these Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers, and what the Indian government should have done, and should now be doing, to protect our last link with our African ancestors.

***

What’s it about?

See above. Lawley explores how the tribes live, how they have been treated in the past, how they are treated at present and suggests what the Indian government might do to protect the remaining tribes. He notes that external contact has destroyed nine of the original twelve tribes and he is justifiably fearful for the existence of the remaining three.

What’s it like?

A deeply personal account of the plight of the Andaman Island tribes, which typically focuses on the tribes through Lawley’s family experiences. I found the content to be a little repetitive in places, with reference to the activities of Lawley’s family members, especially the various schools they attended, but the insights into the various tribe’s lifestyles was as fascinating as the conclusions were saddening. Lawley makes it clear that humanity’s desire to interact with the tribes and to ‘civilise’ them has been devastating, and must stop if they are to have any hope of continuing to live as they wish – in peaceful harmony with the nature on the islands.

Final thoughts

This is a fascinating mix of memoir, history and impassioned plea for a well-thought-through plan that stops treating tribal people as savages in need of civilising and their land as a development opportunity. Lawley concludes on a positive note, that with the right motivation and some difficult decisions, the Indian government could yet ensure the Jarawa people survive and even thrive. It’s hard to accept this positive conclusion, given his own evidence and the current trajectory of the Andaman Island’s governors, but it is certainly worth fighting for.

I was particularly struck by Lawley’s observation that, in seeking to preserve the cultural life of the Jarawa people, we show, ‘recognition of their unique value but [also] of our own self-disgust. In wanting them to be them, we want them not to be us.’ It is true that civilisation is a blessing and a curse; it surely makes sense to avoid inflicting it on a people who have made it clear they wish to be left alone.

Read this book. Then act.

‘A Road to Extinction’,

Jonathan Lawley,

2020, Envelope Books, paperback

Many thanks to Envelope Books for providing me with a copy of this book in exchange for an honest review.

For more information on the Jarawa people and about what can be done to help them survive, visit Survival International. Jarawa (survivalinternational.org)