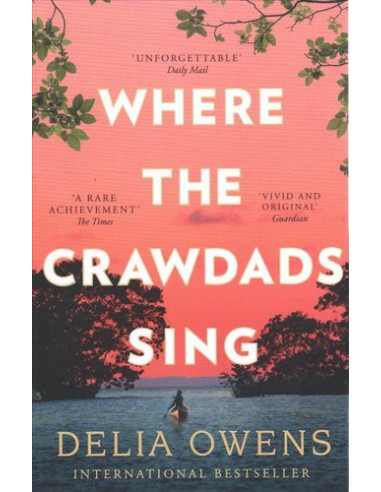

“Kya laid her hand upon the breathing, wet earth, and the marsh became her mother.”

When Kya is just six, her family abandon her, one by one. The hardest loss is her mother, but it is the disappearance of her alcoholic and abusive father that leaves her reliant on the natural world of the swamp and the kindness of a scant few villagers to survive.

This, then, is a tale of survival, a coming of age story that also explores the damage wrought by prejudice and ignorance; a look at how isolation combined with an intelligent nature and an affinity with the natural world can leave a person aching with loneliness.

Let’s start at the beginning.

What’s it about?

As Kya grows, her life is plagued by prejudice and mistrust. The villagers, secure in their houses and their lives, dismiss her as ‘the marsh girl’, perceiving her as feral trash and a threat to their own children, who are forbidden to play with her.

She builds crucial relationships with a local black family and, later, a teenage boy, Tate, who was a friend of her brother, but is fundamentally sustained by her connection with the birds around her.

When Tate abandons her, despite his promises, Kya is devastated once more. Why does everyone leave her? After years of increased isolation, another local boy starts to pay her some attention: Chase Andrews. But Chase is not kind-hearted like Tate and Kya, simultaneously knowing and naïve, is not like the village girls Chase is used to chasing…

Meanwhile, in a parallel narrative set in 1969, Chase’s body is discovered and foul play suspected. Almost immediately, the town’s prejudices provide the likely killer: the Marsh Girl.

What’s it like?

Tender-hearted, atmospheric and, despite some minor flaws, dramatically satisfying. Kya’s heartbreak and reliance on the marsh are vividly depicted and I enjoyed the natural imagery and details about her world.

I defy anyway not to have their heart touched by 6 year old Kya waiting at the end of the lane every day, hoping her mother will return to her, or 7 year old Kya, tentatively building a delicate relationship with her father, only to suffer its brutal collapse. The teenage Kya is perhaps more irritating – as teenagers often are! I was so frustrated by her repeatedly hiding from Tate, though arguably, this is actually a positive sign as it shows how invested I was in the book!

Throughout the book, the narrative switches between following Kya’s development, from 1952 onwards, and the investigation into Chase’s murder in 1969. I found both elements interesting, although Kya’s story is better written. The conclusion to both makes perfect sense dramatically, though specific details are, frankly, ludicrous. Focusing on the characterisation rather than on the finer details of the plot is advisable here!

Final thoughts

I thoroughly enjoyed listening to ‘Where the Crawdads Sing’ as a Bolinda audiobook. (I probably enjoyed listening to some of the dialogue more than I would have enjoyed reading it!)

There have been some suggestions by other readers that Kya could not possibly have managed by herself in her marsh shack, but this ignores the fact that she was looking after herself long before her father finally left her and, I suspect, shows little recognition of how different Kya’s lifestyle was from those of her readers. Could any of my children have coped as Kya did at 6 years old? Of course not, but it just isn’t a relevant comparison to a time and place that was, culturally, very different. My own father regularly reminds me that he was travelling by bus across London when he was only 8 years old; I struggle to let my 8 year walk to school by herself when it’s a 5 minute walk away. Different time, different expectations.

At its heart, this is a moving coming of age story combined with a murder mystery that gives the second half of the novel a clearer shape and focus.