‘Sense and Sensibility’ by Joanna Trollope.

This is the first novel published as part of ‘The Austen Project‘ in which each of Jane Austen’s six major novels have been / will be re-worked by modern authors. You can read my thoughts on the idea itself here and here, but it would be fair to summarise my approach to the whole concept as hesitant. Trollope’s novel was published in 2013 but it has taken me two years and two attempts to read the whole book. Why? Well, where to start?

- I’ve never read anything by Joanna Trollope and don’t think I’m likely to in future. In my mind she’s firmly pegged as an author of frothy socialite romances and that just doesn’t appeal. (Once again: this is only my perception and I’ve never actually read anything else she’s written, so I could well be wrong. And, no, Austen isn’t just an author of frothy socialite romances; she’s a fine satirist able to create utterly convincing characters that I love to read about again and again.)

- The front cover. Do I really want Marianne and Elinor to become modern teenagers, replete with earbuds, bluetooth and addictions to Facebook? Part of the joy of older texts is inhabiting an older world with alien but recognisably English manners and customs.

Although I *think* (this is a tough call) that I dislike this cover even more.

- I doubted whether it could prove possible to translate many of the plot elements to the modern day. What’s to stop Mrs Dashwood getting a job or even signing on?

- And most problematically…the first chapter didn’t grip me at all. Quite the opposite. The prose felt clunky, especially when disseminating information; Marianne nearly using the f-word just felt wrong; and Marianne’s beauty is described thus: ‘Marianne was crying again. She was the only person Elinor had ever encountered who could cry and still look ravishing. Her nose never seemed to swell or redden, and she appeared able to just let huge tears slide slowly down her face in a way that one ex-boyfriend had said wistfully simply made him want to lick them off her jawline.’ Ugh. Just, ugh.

So basically it just felt wrong.

If you’ve read Austen’s original novel (and if you haven’t, why not? What are you waiting for? Go on, off you go, this will wait,) it’s impossible to read Trollope’s take on it without comparing the two. Austen is often portrayed as a writer of romances, but she wouldn’t have thought of herself in that light. Indeed, when her characters do find happiness, it usually happens swiftly and often off-stage; she seems to loses interest in her protagonists the moment their nuptials are agreed upon. They are only truly interesting to her when suffering from unrequited feelings, embarrassment or some other form of discomposure.

You can make the cover pink but you can’t transform the contents into romantic fluff…or can you?

‘Sense and Sensibility’ is focused on the sisterly relationship between Elinor and Marianne as much as it is on their romantic relationships. It is this which suffers wounds and must heal as the novel develops and each woman learns to properly appreciate their sibling’s good qualifies as well as recognising their weaknesses. Moreover, Austen is an excellent comedic writer, and ‘Sense and Sensibility’ is no exception. Take the knowledgeable Mrs Palmer: ‘“Oh dear, yes; I know him extremely well,” replied Mrs. Palmer;—”Not that I ever spoke to him, indeed; but I have seen him for ever in town.”’ Because that’s the same thing, obviously. Or as Trollope’s spectacularly vacuous Nancy Steele might say: “totes obvs!”

Regency rejection becomes YouTube sensation

So what else is new? Marianne is given asthma to explain her fragility; Elinor is made an architecture student to show her disciplined nature. Willoughby becomes Wills and offers Marianne a sports car instead of a horse. Marianne’s rejection is made horribly public via YouTube and Lady Middleton becomes an overindulgent mother of brats that the Steele girls fawn over.

‘”Poor you…It must be awful seeing someone like me with all this lovely future rolling ahead of them, and new friends like Fanny.”‘

Of course, not everything changes. Although Elinor argues that ‘“This isn’t 1810…Money doesn’t dictate relationships”‘, several status and money obsessed characters would like them to. Fanny Dashwood is a wonderfully horrible woman who uses sex and words to persuade her husband to ignore his father’s deathbed wishes; Belle Dashwood is a whirlwind of drama (early on her girls wait patiently as she pauses mid-complaint since: ‘It was clear to all of them, from long practice, that their mother had not finished.’); and Lucy Steele is suitably horrible as Elinor’s super-friendly nemesis (‘”Poor you…It must be awful seeing someone like me with all this lovely future rolling ahead of them, and new friends like Fanny.”‘

There are some difficulties inherent in making the plot suit the modern-day: Marianne’s histrionics seem ridiculous, even bearing in mind her tender years, and her mother’s indulgence of her behaviour is stunning; Ed is understandably but frustratingly unable to explain Robert and Lucy’s behaviour towards the end of the novel; and Ed’s own status with Elinor is astonishing considering the shortness and limited nature of their courtship. In a world where you were never allowed to be alone with your intended, quick marriages made sense; in today’s world such haste is perplexing, though Trollope tries to justify it by reflecting (via Belle and Mrs Jennings) that for many middle class girls a good marriage is still ‘”the only career option”‘.

Final thoughts

There are some amusing touches throughout, but overall I think I would rather read the original again. Somehow I just can’t believe in a modern Marianne, wasting away whole months pining after the feckless Willoughby without someone telling her to snap out of it, or a modern super-sensible Elinor getting engaged to a man she hasn’t even really dated. Despite that, the teenagers’ concerns are convincingly captured and many of the older characters are quite delightful to read about. Charlotte Palmer here is perhaps even more entertaining than in the original.

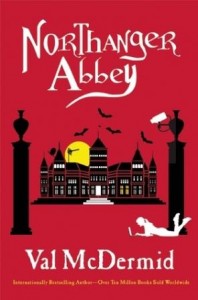

Will I bother reading the rest of the Austen Project novels? Oh yes. And as if to prove that I’m not simply allergic to the concept of Austen rewrites, I am already two thirds of the way through Val McDermid’s Scottish take on ‘Northanger Abbey’ and (minor vampiric distractions aside) am thoroughly enjoying it.

This is definitely my favourite cover. Spooky AND booky. Perfect.

Finally, if you know you’ll never want to read Trollope’s take on Austen, then you really must read John Crace’s take on Trollope. It’s fabulous. And spot on.