“Mum, I’m bored. What can I do?”

As a parent, I have found this persistent cry deeply irritating – and genuinely confusing. My children are surrounded by toys, books, opportunities and activity books. They have access to a garden and to art materials, to siblings, cuddly toys and bicycles. How, I wonder, can they possibly be bored?

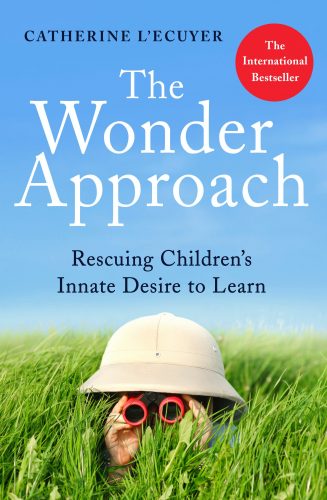

Dr Catherine L’Ecuyer, who has a doctorate in education and psychology, believes she has the answer: today’s children, she argues, are overstimulated by the world, leaving them feeling unmotivated, bored and suffering from hyperactivity and inattention. In ‘The Wonder Approach’ she develops her wonder thesis, explaining why our children are so bored and what we can do about it.

What’s it about?

Essentially, L’Ecuyer argues that in our quest to grow children into adults as soon as possible, we are preventing our five, ten and fifteen year olds from discovering the world with the same sense of wonder they possessed when they were babies and toddlers. To allow children to experience the world with wonder, they need to be treated as children and encouraged to genuinely explore their world with a sense of mystery, rather than treated as mini adults who have to be filled with adult determined knowledge.

From this viewpoint, boredom is a symptom of persistent overstimulation that blunts the child’s appreciation of true beauty, and a bored child a victim of a culture that treats them as a machine to be stuffed full of skills required to function as an adult and stifles their natural wonder.

What’s it like?

Chapters are short, with titles like ‘nature’, ‘pace and rhythms’ and ‘the disappearance of childhood’. Each begins with a relevant quotation or two and focuses on outlining part of L’Ecuyer’s hypothesis and evidence.

L’Ecuyer’s contention that childhood is a completely separate stage of life to adulthood and cannot be rushed is logical, though her final conviction that the adult world needs to better embrace the child’s world is hard to contemplate.

What have I learned?

This is certainly the kind of book that makes you think harder about your own life choices.

I know my children have too much stuff, acquired relentlessly from birthdays, Christmases, pocket money, rewards and, occasionally, mere parental indulgence. I know this is a problem because they are unable to keep their collection of things in order, and that as a result of this surplus of stuff they are not properly appreciative of their toys, books or clothes. They treat them carelessly, knowing that these items are fully replaceable and widely available, and that though their parents will not buy them direct replacements for anything they destroy through carelessness, at some point there will be more Stuff incoming.

I was fully aware of this problem before reading ‘The Wonder Approach’, but I hadn’t considered the idea that such a heap of things could be overstimulating, reducing the ability of my children to develop important executive functions such as choosing where to direct their attention. This is a problem that I know I need to consider carefully how to handle, recognising that I can’t change the wider culture but I have some control over our family culture.

Final thoughts

L’Ecuyer is clear that her book is not intended to be prescriptive, to become another ‘mechanistic approach’ to educating children. Instead, she stresses the importance of the relationships between adults and children, especially secure, trusting relationships with their caregivers, which facilitate a child confidently and calmly exploring their local environment.

This feels like another book (like Sue Palmer’s ‘Toxic Childhood‘) which makes perfect sense but ultimately demands more from parents: fewer sessions with iPads, more trips to the playground; fewer toys with bells and whistles, more time spent playing with your child; and fewer bribes to manipulate behaviour, more time spent understanding your child and what they really need. I’m certain that it’s the better way to raise a child, but it really is the antithesis of our consumer driven, adult needs led culture.

I would definitely recommend ‘The Wonder Approach’ to parents of young children. I think L’Ecuyer is a valuable voice adding to the weight of concerns around modern childhood, how it is treated by adults and experienced by children, and the pressure parents are placed under to ‘enhance’ and ‘speed up’ their children’s ‘learning’ – by providing resources which ultimately sap their sense of wonder and leave us with increasingly agitated children who can stand surrounded by “toys” and wail with genuine distress, “Mum, I’m so bored!”