‘It’s a bit like butchers telling you they’re taking good care of animals.’

Ouch. Peter Wohlleben is not pulling any punches in his discussion of ‘clear cuts’ in forestry, (removing all the trees) but then, why would he when he considers “traditional forestry” to be the very definition of madness – “doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results”. Of course, Wohlleben is a respected and experienced forester himself, so we can trust him to identify the problems and suggest how they can be remedied.

What’s it about?

This is a mixture of fascinating insights into how forests live and thrive, die and recover and an examination of why traditional forestry fails to support true forests (hint: short termism / human desire for extracting maximum profit). I hadn’t ever considered whether trees might communicate, let alone how, and I enjoyed discovering how true forests work together to share water and knowledge. I also hadn’t realised how long trees can live. I can’t find the statistic that surprised me when reading this book, but a quick internet search confirms that some species of tree can live to be 800 years old or more – and can pass valuable knowledge of the local climate down to their tree children. I shall definitely be looking to read Wohlleben’s first book, ‘The Hidden Life of Trees’ to find out more about how trees operate and co-operate.

The closing paragraph of the introduction precisely sums up the overall message of the book: ‘we cannot create forests…A better way to help trees is to step aside and allow natural reforestation to take its course’. Organising his material into three sections – how trees and forests work together (including to cool the planet, which is not as simple as you might think!), the problems causes by conventional forestry, and the way forward to truly protect trees – Wohlleben seeks to convince us of his thesis.

What’s it like?

Perspective shifting. What if we truly appreciated what value trees add as forests, rather than their commercial value as timber? Inspiring, because Wohlleben believes that trees are so amazing that we have not yet destroyed the possibility of forests, despite having destroyed so much forest already, as long as we change our approach to forestry now. Frustrating, because he tears down simple certainties and replaces them with a vague sense that greater privation will be our future.

Have you ever admired a politician or community leader who’s helping the environment by planting new trees? Let’s pause a moment. Are these trees intended to replace an old forest? What happened to that old forest? Who was responsible? Who will be looking after this new forest? Will they be changing their approach in light of their previous failures? Are the new trees native seedlings who will lead long lives and enrich local biodiversity? Or have they been selected for their quick growth, chunky branches and thin, straight trunks, easier to log and destined to be chopped down before they’ve even reached their adolescence in tree years? I imagine even optimists can guess the gloomy answers. It’s depressing but unsurprising to find that rhetoric around protecting forests is usually greenwashing a desire to protect profit margins.

Similarly, if you’ve ever felt good about purchasing wooden products because they are ‘renewable’, Wohlleben asks us to consider how long these products last, how much carbon dioxide they release when they are no longer wanted versus how much carbon they could have stored over their natural lifespan, and to understand that, in terms of environmental impact, burning wood is worse than burning coal. This transformation of easy positives into more complex (and frequently negative) equations could easily become depressing, but Wohlleven focuses so strongly on the awe inspiring eco systems forests build that I never felt preached to.

In fact, the forester is careful to resist making any concrete suggestions about what a life with less timber in it might look like, except for a brief reference to the usefulness of owning a bidet and a slightly longer segment advocating a reduction in meat eating (to allow for land currently set aside for pasture to be rewilded). I found this a little unsettling – what does this new world look like? How will it work? – purely because I’m a planner. I like to have a plan; I wanted more details about how a world with significantly reduced access to timber works, but ultimately that is outside the scope of this book. Furthermore, Wohlleben’s final advice is distilled into a strong conclusion by Professor Pierre Ibisch, who notes that, ‘We desperately need to learn how we can manage our ignorance better…Instead of believing that smart engineers with their technological solutions will save us’. Essentially, trust nature; she knows what she’s doing. And maybe invest in a bidet.

Final thoughts

It’s worth noting that this book’s subtitle is ‘how ancient forests can save us if we let them’. Wohlleben and Ibisch are in no doubt that, even if all ancient forest is destroyed by logging, once humanity has destroyed itself, the trees will survive and regroup. This book is not a plea to save the trees or even for us to plant trees (although Wohlleben does advocate for a tree or three in domestic gardens); instead we are urged to recognise the amazing eco system that trees in forests provide and to just step back, admire and reap the benefits, instead of having the arrogance to think that forests, which have slowly recovered from myriad natural disasters over millennia, need our “assistance” in the form of, erm, cutting down and burning all the trees, thereby condemning ourselves to run away climate change.

Towards the end of the book Wohlleben advances a passionate argument for campaigning for truly wild spaces – wildernesses – instead of being contented by sanitised, commercialised “nature” spaces. I found this a particularly interesting argument, as it is true that a lot of “nature” has been harnessed for profit and is maintained with that aim in mind, rather than allowing truly natural spaces to evolve over time – and thereby become less accessible to humans!

As you can probably tell, I found this a really interesting read. Wohlleben is German and so the book focuses on German forestry practices, but he states that these are basically universal – that the Germans have exported the current model of forestry very successfully. I can only hope that the new forestry course he has worked to establish is a great success and that there is a shift in forestry circles worldwide to value trees as forests rather than simply as timber.

There’s so much more I could say…but instead I’ll just suggest that anyone with an interest in the natural world would enjoy reading ‘The Power of Trees’.

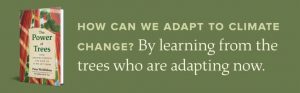

‘The Power of Trees’,

written by Peter Wohlleben,

translated by Jane Billinghurst,

2023, Greystone, paperback

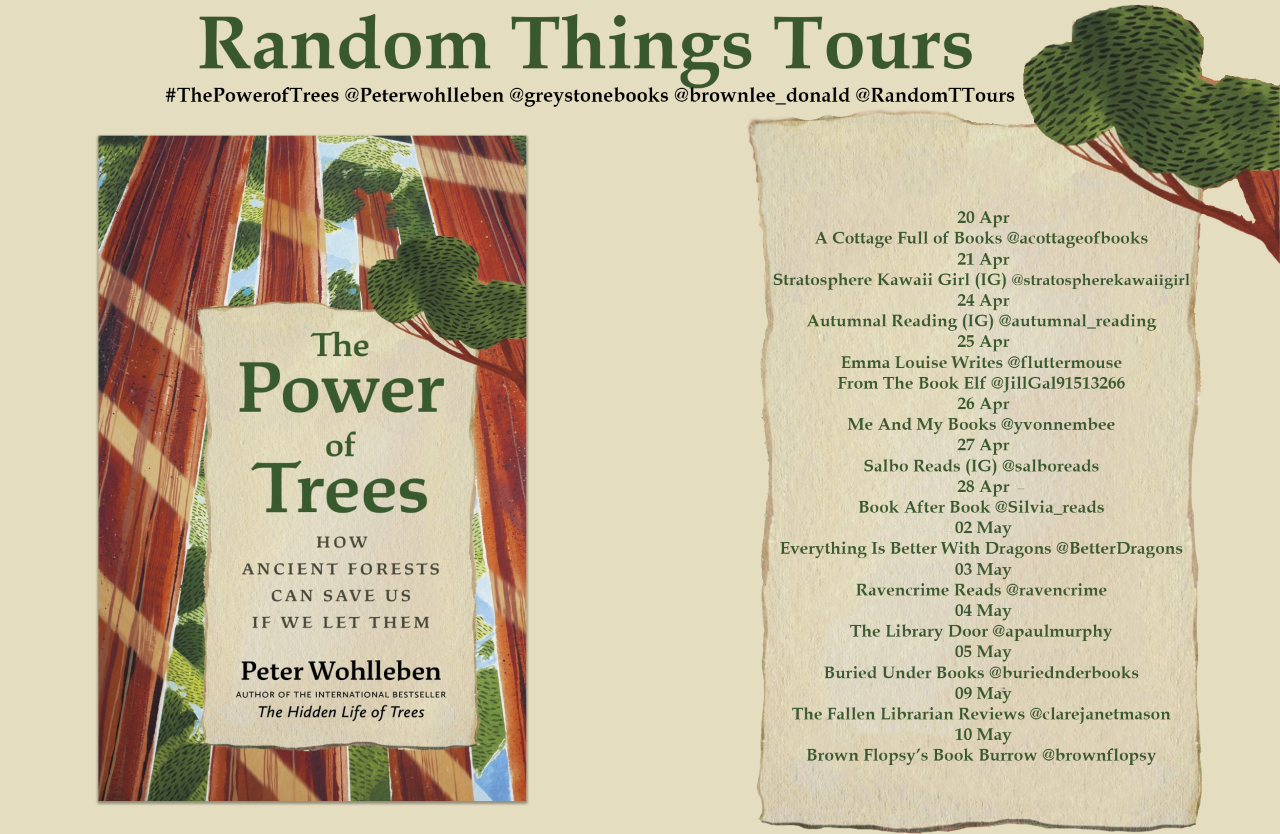

Many thanks to the author, publisher and Anne Cater’s Random Things Tours for providing me with a copy of this book in exchange for an honest review and a spot on the blog tour.

Want to know more? Follow the tour:

1 Comment

Thanks for the blog tour support x