‘Pride and Prejudice’ is my favourite Austen novel.

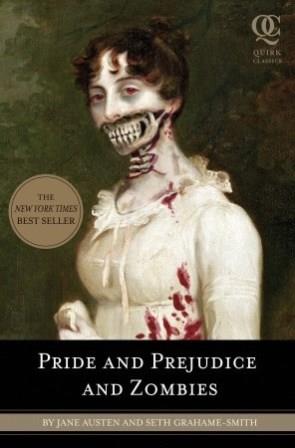

So when I heard some impudent writer had decided to add zombies to the original in an attempt to ‘transform a masterpiece of world literature into something you’d actually want to read’, I was torn between horror and intrigue. Where would the zombies fit in the already crowded ballrooms? Would they have the decency not to try to eat their social superiors? Would any of the Bennet sisters escape the matrimonial trap by falling victim to the “unmentionables”? Was Austen turning in her grave? (Or indeed, getting out of it and having a wander about?) In order to answer these important questions, I felt obliged to buy the book.

The original

“It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a large fortune must be in want of a wife.”

If you’ve never read ‘Pride and Prejudice’, (and have spent your entire life steadfastly ignoring every cultural reference to it,) it’s worth knowing that the novel focuses on the matrimonial hopes and adventures of three young women from a family of five sisters. As their father’s estate is entailed away from them, and there are no brothers to support them, the girls must make advantageous marriages if they are to avoid sliding lower in society. Other characters are introduced to counterpoint the main relationships and help to express the writer’s own perception of courtship and marriage. This might sound rather dull, but it really isn’t! Want to know more? Then go here.

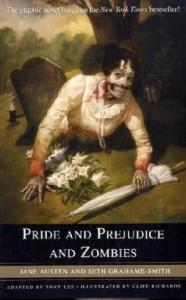

Over the years, a truly ridiculous great number of adaptations have been created, either for film or television, as interest in Austen’s most famous work continues to thrive. There are also a great many prequels and sequels in novel form. This is one of the latest additions to the burgeoning oeuvre of revisionings: a zombie ‘mash-up’ featuring Austen’s full text, adapted and expanded to incorporate zombie mayhem.

The zombies

A mysterious plague is afflicting England in the form of the “unmentionables”: the dead are returning to life and eating the living. Our heroine, Elizabeth Bennet, is determined to help wipe out the zombie menace from the quiet village of Meryton, and her sisters fight beside her when required. They are all trained in the deadly arts, although the younger girls are perhaps less disciplined. Mrs Bennet wants to see her daughters married and is quite excited when a handsome young man moves into the neighbourhood, but her husband is more interested in keeping the girls alive than matching them with suitors. Gradually, Elizabeth becomes more involved with the young man’s rather haughty friend, Mr Darcy. Can they overcome their ill conceived pride and prejudice (and multiple zombie attacks) to recognise their suitability?

http://nerdapproved.com/approved-products/pride-and-prejudice-and-zombies-and-postcards/

So it really is P&P + zombies. I was particularly intrigued to see how the fighting would work in a society in which ladies were expected to look and act extremely demurely. I imagine it’s quite a challenge to appear lady like while slicing off a zombie’s head. Of course, the original P&P was written and set during a period when England was at war, and barely touched on the dramatic background. The presence of the militia was an excuse for flirting and partying rather than agonised accounts of death and destruction. (In fact, Austen has been criticised for this absence, but she wrote what she knew, and she did that very well.) I wondered whether the zombies would form part of the background, and half expected the odd reference to the ‘plague’ to crop up without much actual action – but I was wrong. Very wrong.

The mash-up

“It is a truth universally acknowledged that a zombie in possession of brains must be in want of more brains.”

Grahame-Smith’s style involves taking most of the original text and tweaking it, although there are substantial additions elsewhere. The plot is largely unchanged, although the fates of some characters are understandably rather different! The major events all occur, although they frequently feature zombie intrusions, so you can read the story easily and enjoy the added zombie mayhem.

“It is a truth universally acknowledged that a zombie in possession of brains must be in want of more brains.”

However, one significant change that I noticed immediately was a lack of subtlety in Grahame-Smith’s amendments. As I have mentioned before, it’s Austen’s concise, subtle irony that makes P&P so enjoyable. In the very first chapter, Grahame-Smith creates a much harsher Mr Bennet, who calls his wife a “silly woman” and instructs her to “prattle on if you must”. It may not sound like much, but it transforms the character from a quietly put upon husband to a rather harsh one. It also seemed to show a lack of faith in the reader: we must be told that Mrs Bennet is silly and that her husband finds it hard to be patient with her; we may not have noticed otherwise. (Newcomers may be shaking their head at my apparent pickiness, but aficionados of the original will surely understand my own irritation.) This lack of subtlety was apparent in several places throughout the novel where Grahame-Smith adapts Austen’s text to make the implicit explicit. (Elizabeth is also crueller: rolling her eyes and yawning at Mary to show her boredom.) In doing so, he loses the true flavour of Austen’s writing, which is a shame.

There’s also a graphic novel.

Similarly, there are hints from as early as chapter four that Darcy’s cold demeanour is somewhat justified. Does the writer believe that without these clues we will write Darcy off too early? (Austen wanted the reader to learn a valuable lesson here, although there were some subtle clues along the way.) Does he believe that a modern reader has to have these large hints about what’s coming up next in order to keep reading? Once again I felt that these additions actually detracted from the original quality of the writing. (Besides, there is no evidence that Darcy was ever “a young man of merry disposition”; Austen wanted us to see Darcy change and grow in response to his love for Elizabeth and her insights. In this version, Darcy loses his complexity.)

Sometimes zombies fit surprisingly well into the story

However, my criticism of these changes aside, I initially quite enjoyed reading the story. I liked the way that the writer adjusted details in the original text to fit in the zombies (“Don’t keep coughing so, Kitty, for Heaven’s sake! You sound as if you have been stricken!” and “Within a short though perilous walk of Longbourn lived…”) and kept the references to the “unmentionables” suitably dignified for the period. The writer also makes use of Austen’s understated manner at times to return us to the original story: “Apart from the attack, the evening altogether passed off pleasantly for the whole family.” These neat links made me smile and I enjoyed the way that the zombie details were neatly integrated into the original plot.

And soon there’ll be a film.

The fighting scenes are described clearly and in detail, but without gore. In this sense, I feel that they are true to the original as the added scenes are recounted in a suitably formal style. Elizabeth and her sisters have almost preternatural strength, it seems, having trained in the Orient. While their abilities are perhaps rather unbelievable (“She picked him up with one arm and lowered him into the coach [from the roof]”,) it is a story with zombies in, so suspension of belief seems not only fair but rather fitting! Grahame-Smith often uses the zombies to reveal aspects of characters that do fit with Austen’s original conception. Lydia’s carelessness is revealed by her desire to simply ignore the zombie menace unless forced directly to fight. Lady Catherine uses her training to try to defeat Elizabeth’s sense of self in the same way that she uses other details to dismiss and belittle her.

And sometimes they don’t.

Ultimately, though, I got bored. I became frustrated with the changes that removed Austen’s subtle artistry and shouted truths at the reader. I became irritated by the zombie action interrupting the well crafted story I was so familiar with, and some of the events just seemed too ridiculous. (One character spends weeks turning into a zombie…but nobody except Elizabeth seems to notice, despite the zombified woman living near the famous zombie killer that is Lady Catherine. Sorry. No. Too silly.) I found that it took me months to finish the book as I would read bits before bed, but never really ‘got into’ the storyline again. Perhaps I had simply devoured too much of the book initially and ruined my appetite for it.

There’s a ‘reader’s discussion guide’

“Some scholars believe that the zombies were a last-minute addition to the novel, requested by the publisher in a shameless attempt to boost sales. Others argue that the hordes of living dead are integral to Jane Austen’s plot and social commentary. What do you think? Can you imagine what this novel might be like without the zombie mayhem?”

“Some wore gowns so tattered as to render them scandalous”

Obviously, this 10 question guide is included just for laughs, but some of the questions are interesting to consider – although I’m not entirely convinced that Austen intended Elizabeth Bennet to be “the first literary lesbian”…

Also included are illustrations, usually every 15-30 pages. The darkness of these helps to lend a certain sense of threat to the novel – although this is by no means a scary tale. The illustrations focus on the zombie action and serve to reinforce the bravery of the humans – although, again, this is not a story of epic heroism. They’re a nice touch and another nod to how original publications of P&P would have appeared.

Final thoughts

Although I initially enjoyed the weaving of zombies into Austen’s rich tapestry, it’s a conceit I lost interest in about a third of the way through. Perhaps my aversion was caused by my intimate familiarity with the original; I found it irritating in places where I felt that Grahame-Smith had destroyed the subtlety of the original. However, I’m not sure that I would have bothered to read this work if I hadn’t read the original P&P as I feel that a large part of the initial enjoyment does arise from seeing how the zombies are added in.

I suspect I would have found the novel as a whole more digestible if I had consumed it in smaller portions. Still, definitely worth a nibble if you’re an Austen / P&P fan. Possibly less likely to whet your appetite if you’re approaching it from the perspective of a hardcore zombie fan. Or is regency romance something zombie enthusiasts have felt they’ve been missing out on?

And of course, if zombies aren’t your thing but mash-ups are, you could try ‘Sense and Sensibility with Sea Monsters’. And no, I’m not kidding.