As soon as I spotted this, I knew I had to buy it.

One of my favourite books – ‘Pride and Prejudice’ – now had a sequel in the crime genre? Fabulous. I had never previously read anything by P. D. James but recognised the name and was aware that she was a popular and well-established crime writer.

Could this be as good as it promised? Sadly, the answer was no, not quite.

Have you read ‘Pride and Prejudice’?

If not, fear not, as James spends the first chapter essentially recounting the plot of the original novel, with a few embellishments to bring the story up to date. (For instance, perhaps surprisingly, dull Mary has married reasonably well, while the more engaging Kitty is the sole remaining daughter at Longbourn.) This section could perhaps have been handled better. While James succeeds at conveying the necessary background information, attempting to do so as part of the story results in some rather contrived attempts at humour.

Information is primarily conveyed through an account of how the local gossips interpreted the events that befell the Bennett family. Of course, Elizabeth only married Darcy for his estate. Of course, no one believed that Wickham had actually intended to marry Lydia. This is perhaps funnier if you have read the original, but it does all feel a little awkward. I would rather have read a summary of the plot as a separate element so the story could have a more dramatic starting point. That said, handling information from a prequel is always a challenge and James does at least try to do this in an engaging manner. Newcomers and afficonados alike will be mildly entertained by the opening chapter. Other relevant information is woven into the text relatively well at appropriate junctures and feels less heavy handed than the opening chapter.

So what did happen in ‘Pride and Prejudice’?

Essentially, Austen explored early 1800’s attitudes to marriage, criticising lust, condoning (some) financial sense and encouraging romantic attachments based on a study of charater, allied with a good dose of common sense and money. She established the characters of Jane, Elizabeth, Darcy, Bingley, Lydia and Wickham. Want more details? See my comments on P&P here.

Crucially, Austen’s style is satirical and the story is most frequently developed through conversations which allow characters to reveal their true natures to the reader. Elizabeth and Darcy both learn valuable lessons throughout the novel and it’s often hailed as a great romance, but it’s primarily a rich social comedy with many minor characters who provide great entertainment.

What happened next?

According to James, there have been six years of happily ever after since the events of P&P. Elizabeth has two healthy sons, Jane and Bingley also have children and now live further away from the rest of Jane and Elizabeth’s rather embarrassing family. Even Lydia and Wickham seem to have done reasonably well: he has been celebrated for his heroics in battle and they both somehow survive on handouts from unnamed sources. But of course, this is a murder mystery, so everything is about to change – or is it?

Photo credit: Neal Fox, The Guardian, Death Comes to Pemberley Digested by John Crace

On the night before Lady Anne’s ball, an annual celebration held at Pemberley, an unexpected carriage comes clattering desperately up the driveway. Out of this harbinger of doom tumbles a hysterical Lydia, screaming that her husband has been killed. After recovering from the displeasure of receiving this definitely uninvited guest, Darcy and two other males go out to investigate. Yes, there is a body in the woodland. (One can only imagine the horror of Lady Catherine: the shades of Pemberley are now polluted indeed.) Darcy seems to have found the murderer standing over the deceased body and admitting responsibility, but Darcy doesn’t believe that he is guilty…so who is? And can Darcy prevent a wrongful conviction for murder?

In a minor subplot, the lovely Georgiana has two suitors: an Earl and a Baronet. Lucky girl. Elizabeth thinks she knows who Georgiana favours, but will Darcy allow his sister to marry where she wishes? As the blurb promises that Darcy and Elizabeth’s perfect marriage is “threatened” by events, it seems likely that this may be the cause. Will Darcy’s pride cause trouble between them once again?

So is it any good?

The ineptness of the “investigation” was the first thing to strike me as I read: Darcy moves the body from the wood to an outbuilding on his property, potentially destroying valuable evidence, while the local magistrate accepts a rather pathetic alibi from Darcy’s cousin simply because he is so respected. Writing a story set in the past allows James to make a few jokes (“I don’t suppose you have yet found a way to tell one man’s blood from another”) which may raise a wry smile as the reader thinks about the progress we have made. I found that reading this made me feel grateful that times have changed and people are (typically) no longer automatically considered innocent due to their status. In fact, I wanted someone of high status to turn out to be guilty in this novel just so that Darcy could REALLY learn a lesson about status and morality, but, sadly, James is not that daring.

Instead, the murder mystery itself is quite a disappointment. While Darcy is adamant that the chief suspect cannot be responsible, there are no other convincing contenders for the role of villain and there is no real investigation. Witnesses give their evidence, most of which the reader has already witnessed, and “justice” appears to be unobtainable. Eventually, James relies on Dickensian coincidence to allow for a shocking last minute court room announcement that actually makes little sense. I found neither the who dunnit nor the why they dunnit to be convincing. Clearly, James herself felt that this might be an issue as she has Darcy question one of the other characters about this series of events. They reassure him that it is all perfectly plausible, but I didn’t find it so. I like to be able to guess at the backstory and villain when reading crime fiction, and although I could guess at some of the denouement here, I felt that too much was held back and only revealed at the end. In fact, the killer is revealed 60 pages before the end of the 310 page book. When you need 50 pages of conversations between characters to unwrap the plot, it does suggest that there might be a tad too much plotting.

And yet I’m still tempted by the DVD.

As this is meant to be a crime novel, I feel I ought to say more about the crime element, but there is really very little to say. The denouement revolves around typically nineteenth century concerns: the seduction of young maidens, the difficulties produced by their illegitimate children and the machinations required to avoid public shaming. This is all very appropriate for the period, but it doesn’t grip readers in the same way that a more modern resolution could. It’s difficult for readers today to understand the sheer horror attached to the mere thought of an unvirtuous woman. (Darcy practically chokes on his loathing for Mrs Younge, a key figure in the denouement, who blackmails young men after sleeping with them.) I think the story could have been gripping if told from a slightly different perspective. As it’s written, James relies upon multiple narrators who reveal bits of the story to Darcy, but most of the main characters are denied a voice. As such, the emotions seem very muted and the tone is rather factual. Disappointing.

So what about the Austen angle?

I thoroughly enjoyed the brief references to other Austen novels (fans of Anne Elliott will be glad to hear that she is doing well, as is Harriet Martin) and the occasional comic touches that James adopted (“Although the library shelves, designed to Darcy’s specification and approved by Mr Bennett, were as yet by no means full, Bingley was able to take pride in the elegant arrangement of the volumes and the gleaming leather of the bindings, and occasionally even opened a book and was seen reading it when the season or the weather was unpropitious for hunting, fishing or shooting.”)

Ooh, I LOVE this cover.

Charlotte manages Mr Collins: “She consistently congratulated him on qualities he did not possess in the hope that, flattered by her praise and approval, he would acquire them.”

However, I felt these were moments that gleamed in the dark, for the rest of the characters were rather dull. Rather than hearing Elizabeth’s voice throughout, James must use Darcy as she recounts the masculine world of the inquest and the court room. Unfortunately, Darcy’s character is not as lively as Elizabeth’s; his emotions are all guilt and concern for propriety. He simply doesn’t create as engaging a window on the world.

Sadly, even Elizabeth has been tamed. Despite the promise of the blurb, her marriage is in no way threatened by the events of the novel. Rather than the anticipated scenes where Elizabeth instructed her husband not to be blinded by pride and to let Georgiana marry where she will, this promised plot development fizzles into nothingness. The previously spirited Elizabeth, now in charge of Pemberley’s future, simply defers to her husband and hopes he’ll have the sense to see what’s right. *

Who is Elizabeth Darcy?

I think this is quite a serious problem with the novel as a large part of appeal Elizabeth Bennet’s appeal in the original P&P was her willingness to say what she thought and her refusal to simply bow to the desires of established hierarchies. Here, she actively works to promote them – when she is seen. Despite repeatedly assuring the reader that Darcy and Elizabeth are very much in love, they spend barely any time together over the course of the novel. Elizabeth is restricted to the feminine sphere (her house and her flower arrangements) while Darcy engages with the murder enquiry. I thought this was a disappointing conclusion to what had promised to be a more equal marriage.

The start of a happy marriage?

When the couple are reunited at the end of the novel, James seems to have panicked that there was not enough reference to P&P in the story. Suddenly, Darcy is apologising for things he said and did six years previously and Elizabeth is lovingly forgiving him. I found this rather odd, as this was all resolved satisfactorily at the end of the original novel. I also wonder how well this would work with readers who have not read the original. After all, you don’t usually expect the last ten pages of a book to return to the previous novel in the series.

We are also reminded at the end that the couple have two children. I did find myself forgetting this as I read; due to the fashions of the time, the children live in the nursery and their parents basically have visiting hours. This is not a criticism of James’ writing as she is simply being true to the historical setting of her novel, but it is once again a little disappointing to see the revolutionary Elizabeth Bennet treating her own offspring as roughly as worthy of her attention as her plans for Lady Anne’s party.

Conclusions

Although I found this perfectly readable, I didn’t find it either as interesting as I would want a crime thriller to be or pitched quite as I would like an Austen adaptation to be. I liked the premise and the flashes of Austenian wit, but, sadly, it failed to really excite, interest or convince me.

And yet…a quick flick through the pages reminds me of how perfectly Austen-like James’ prose can be, and I’m conscious that my hopes for Elizabeth’s marriage and life probably mesh better with my modern desires for her than with Austen’s own thoughts and intentions. Perhaps one day I’ll reread ‘Death comes to Pemberley’ and think I was unduly harsh in my review.

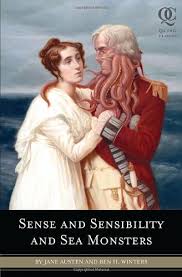

In the meantime, if you’re a big P&P fan looking for a modern twist but not sure about this sequel, you could always try Seth Graeham-Smith’s entertaining ‘Pride and Prejudice and Zombies’. Yes, zombies. ‘Whatever next?’ you ask. ‘Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters?’ Erm…yes actually. Go on. Google it. You know you want to.

Because…Austen’s original novel lacked tentacles?

What do you think? Should P.D. James have written a sequel to P&P at all? Are you tempted to read it? Once again, if not, you should read John Crace’s digested read instead. It’s wickedly on point.