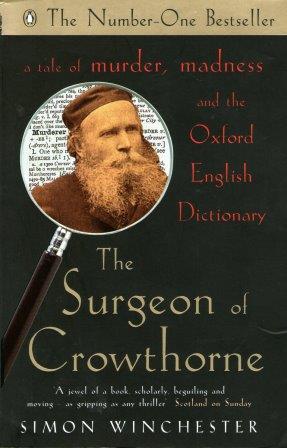

A tale of murder, madness and The Oxford English Dictionary.

Such is the full title of Simon Winchester’s intriguingly titled ‘The Surgeon of Crowthorne’, a book all about, well, murder, madness and the OED, though there’s more on the latter than the former.

What’s it about?

Lexicographer James Murray is attempting to compile the first OED, a vast undertaking that eventually consumes 70 years and is not completed until 12 years after his death. During this struggle, Murray communicates extensively with many keen contributors, but builds a particular friendship with one: Dr William Minor of Crowthorne. As well as being a star contributor to the important dictionary, Minor is a lunatic, consigned to stay indefinitely at Broodmoor lunatic asylum after committing a murder.

This is a book partly about their friendship, partly about that murder, but mostly about the making of the mighty OED.

What’s it like?

Detailed, thoughtful and written in such a way that you are drawn into Minor’s affairs with a sympathetic eye.

It’s slow-going as the book has multiple beginnings: an extract from a call for contributors to the dictionary is followed by a preface; the preface briefly outlines the mythology surrounding Murray and Minor’s first meeting and implies this book will offer revelations regarding the truth of that meeting; this is followed by a chapter detailing the life and murder of George Merrett, which of course introduces Minor; this is followed by a chapter outlining James Murray’s early life and the beginning of his involvement with the dictimary; THIS is followed by the murderer’s relevant history until that point; then there is a chapter outlining the very beginnings of the concept of the new dictionary. In short, nearly 90 pages have passed before the story truly gathers steam as some of the key participants (Murray and the dictionary) properly come together.

Winchester delights in minor details and speculation.

Such length is not simply the result of having to introduce various characters – including a book! – but is rather due to Winchester’s delight in minor details and speculation. He writes that Minor ‘selected a pen with the very finest nib’ to send his first words to the dictionary. Perhaps. Even probably. And perhaps not. More importantly, he suggests that the view from Minor’s suite at Broodmoor must have meant Minor’s sentence ‘cannot have seemed altogether a nightmare’. Hmm. I’m not sure a good view, even an excellent view, would detract one’s attention too much from the horror of being committed indefinitely to a lunatic asylum in a foreign country. Still, such intimate touches help to bring the characters and the events to life, making potentially very dry material more engaging, though they do sometimes lend the writing a slightly fictional air.

Perhaps appropriately, the ending is also a drawn-out affair with a chapter called ‘Then Only The Monuments’, which is primarily concerned with the deaths of the major characters, followed by a postscript, followed by an author’s note, followed by suggestions for further reading. This, then, is a leisurely read, one which will reward readers with the time and patience to piece together all the relevant details in their minds.

Final thoughts

I had never realised dictionaries took so long to write and found the details Winchester included about the methods used were generally interesting, though I skimmed some of the biographical bits (I don’t much care where Minor or Murray grew up or how many siblings they had) and felt there were more examples of definitions than I particularly cared for. (It seems I am not a lexicographer at heart.)

This will be of most interest to those with a love of words and a love of history, though there is also some interesting discussion about Minor’s illness, finally revealed to be what we would now call schizophrenia. Towards the end of the book in particular Winchester discusses Minor’s illness in broader terms than in the preceding chapters, considering what triggers such mental disorders as schizophrenia and post-traumatic stress disorder, and how they might be treated differently today.

Overall it’s a pleasant meander through a bit of literary history, replete with imaginative embroiderings at the edges.