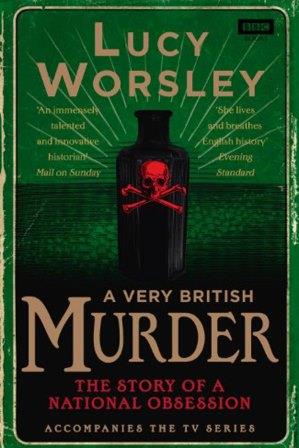

Have you ever considered murder as a form of entertainment?

How about murder as an art form? Popular cultural historian Dr Lucy Worsley has.

What’s it about?

‘A Very British Murder’ is described in Worsley’s introduction as ‘an exploration of how the British enjoyed and consumed the idea of murder, a phenomenon that dates from the beginning of the nineteenth century and continues to the present day.‘ This exploration is bookended with Thomas de Quincey’s satirical essay ‘On Murder Considered as one of the Fine Arts’ and George Orwell’s essay ‘Decline of the English Murder’ and considers how definitions of and performances of interesting murders have changed from Georgian, through Victorian and during the inter-war years. Concluding her examination with Orwell means Worsley does not examine televisual representations of murder, which it would have been intriguing to read her thoughts about.

What’s it like?

Fascinating. With a light, deft touch Worsley exemplifies with well-known murder cases how attitudes have changed since the British population first felt secure enough in their homes and lives to turn to murder as a form of entertainment. The Georgians were fascinated by charismatic, anti-heroic highwaymen; Orwell’s ‘perfect murderer’ was a Dr Crippen like figure, a middle-class professional who turns to violence to avoid shame; today’s most fascinating murderers are psychopaths, remorseless, nihilistic serial killers. Why? Worsley traces the changing attitudes of the public as criminal sanctions changed and the modern police force developed.

Initially, accounts of murders, including confessions from the scaffold, were reported in brief newspapers called ‘broadsides’, and while we may like to feel that we have become more civilised since public hangings were abolished, it seems we have changed little in our thirst for decoding danger at a suitably safe distance:

‘No horrible detail was overlooked by the printers of the broadsides, and their careful technical language and close observation is similar to the police procedural fiction of today.’

‘No horrible detail was overlooked by the printers of the broadsides, and their careful technical language and close observation is similar to the police procedural fiction of today.’

What’s to like?

I found it particularly fascinating the way that crime has traditionally been used to reinforce social norms and, perhaps contrary to our initial presumptions, to reinforce our fundamental feelings of secuity. After all, a criminal who has been hung will hurt no-one else. The role of the broadsides, often denounced for their shameful grubbing around in gore, were in fact always presented in a way designed to reinforce core morality and usually contained (made-up) confessions so ‘no reader of broadsides could have been left without the impression that to turn to crime leads inevitably to shame, repentance and death‘.

Similarly, Worsley examines how the ‘Golden Age’ of Detective fiction aimed to create a simple, safe world with genteel murders that were always resolved and created a comforting antidote to the recent horrors of war. This seems simple common-sense, but it’s still interesting to read about the unconventional lives of those who developed the genre.

Final thoughts

This is very easy to read and discusses a number of well-reported crimes and criminals, authors and works (inevitably including some spoilers, so take care if she begins to discuss a book that’s coming up soon on your TBR list). If you’re looking for more in-depth accounts of indivduals and events then there’s a helpful biography, but I would occasionally have liked a little more detail about the crimes discussed. That said, this is intended to be an overview and it excels at that.

Conversely, there were a few instances where particular facts were repeated in another chapter, which I found mildly irritating. (This may be because the idea behind this book was initially presented as a TV documentary. I find that these tend to assume readers have no short-term memory, or perhaps that they are constantly popping off to the kitchen to make more cups of tea, so they repeat the key facts frequently, especially after an ad break.)

If you’ve read social historian Judith Flanders ‘The Invention of Murder’ (2010) then you may find this book doesn’t add much that’s new to your understanding of this area, since Worsley references Flanders’ book extensively. (That said, I haven’t read ‘The Invention of Murder’ so could well be overestimating the extent of overlap.)

These are extremely minor quibbles and I found this an enjoyable read with plenty of interesting connections between popular literature and crime.