I’ll be honest:Â this was not a book that appealed to me.

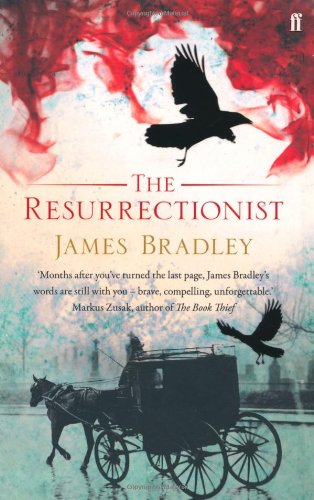

In fact, if this hadn’t been a book group read, I would never have lifted it from its shelf. The title suggested fantastical doings; the blurb refers to our hero, his “nemesis” and his “sinister” travels in Georgian London that will “change his life forever”. To add insult to boredom, there was a Richard and Judy sticker slapped onto the top left hand corner. The only redeeming feature was the recommendation by Markus Zusak, whose novel, “The Book Thief”, I had really enjoyed.

What’s it about?

So we have a set of clichĂ©s and a novel that’s keen to assert its historical credentials.

Gabriel Swift arrives in London to study with a great anatomist. Despite initially appearing likeable and innocent, he is drawn into a downward spiral of events, dismissed by his master and pulled into London’s underground.

(Why are nearly all journeys in books âlife changingâ? Most of my journeys are simply necessary and, if by train, delayed.)

What’s it like?

Given the sheer number of books published each year, I appreciate asking for genuine originality is impossible. However, this plot felt like it had done the rounds a few times, lost its hat along the way, and was now limping into a new paperback edition. But the blurb suggested a dramatic and intense novel… which this was, so it did prepare me for the content.

That said, this blurb appears to be an overview of the whole plot rather than simply setting up the opening situation, and this meant I spent a couple of hundred pages waiting for Gabriel to get fired.

That said, this blurb appears to be an overview of the whole plot rather than simply setting up the opening situation, and this meant I spent a couple of hundred pages waiting for Gabriel to get fired. I found this frustrating, as if I’m expecting something significant to happen I do expect it to happen rather earlier on – as a general rule. As for the âjourneyâ, by the time it happened Iâd forgotten it was supposed to. If youâre a tad on the impatient side yourself, you may understand my frustration.

The coldness and casual detachment, in contrast to the grisly images portrayed, is a little unsettling. The scene brings to mind Burke and Hare. I did like this opening – I thought it was very engaging and I began to hope that I would enjoy the story rather more than I anticipated.

Bradley has a highly descriptive style when describing physical movement and this is employed throughout:

âThe teeth bite into the bone with a wet, splintering rasp, small flecks of meat and bone scattering before it, spattering the aprons we each of us wear.â

I will forgive a book much if it is well written and the teacher in me couldn’t help but think this would be a great example for my pupils on how to describe events in detail. (The teacher in me never seems to sleep, much to my husbandâs bemusement when he sees me clipping out an advertisement or an article from a magazine. âThis will work SO well for 9B,â I tell him happily.)

I thought the descriptive style was one of the novel’s strengths, although I had little sense of place when reading; London is constantly foggy and gloomy but thatâs about it. Perhaps, as an Australian author, Bradley found it difficult to write about a setting that was in another century and country.

I was pleased the diction and vocabulary were suited to the era without seeming forced or awkward; I found it was easy to read but also gave me a sense of an earlier time.

All the chapters are very short – only three or four pages, often only two. In fact, they donât even seem to be chapters, as there are no numbers or headings, just large gaps and lots of white page. I liked the sense of real pace this gave, even though it contrasted with the narrative style.

Gabriel spends much time observing and reflecting upon minor moments (a colleague sketching or a friend chatting) but despite this reflective style, it feels like no word is wasted. We are never treated to Gabriel’s actions unless they are invested with portent. To me, this gives the text a dramatic quality, as if we are watching a sequence of scenes play upon a stage. Everything felt relevant and potentially significant… and yet the flighty nature of the story, picking up a moment here before moving on to a totally different moment elsewhere, gave an unusual “feel”.

Of course, some readers could find this irritating – especially since, as the novel progresses, it starts to seem that words have been wasted once certain characters vanish or fail to attain importance.

Beside the main character, there are several minor parts. Many of them are imbued with a certain significance, but they tend to fade away. By the end of the novel I was rather frustrated since I felt that Bradley had been preparing me for denouements which never came, and what appeared to be hints preparing the reader never went anywhere. It appeared that most characters existed simply to mark Gabrielâs descent into darkness.

Gabriel himself is a bigger problem. As my book group decided unanimously, he is a passive wimp. It appears that Bradley wanted to show that people are neither good nor evil, but make decisions that have consequences. Great. Except that Gabriel doesnât really make decisions. Things happen to him and it is nearly impossible to understand why he reacts in the way that he does. He falls into opium addiction, sex with an actress/prostitute and employment with a thoroughly nasty man â and this is just the start. I was genuinely shocked by some events as the novel charted his descent into degradation, but I couldnât empathise with him as a character because his reactions were so strange. Partly this was the opium; partly it was the way in which everything struck him as inevitable. He wasnât an engaging or interesting character for me and I felt that this was a real flaw in the story. As I didnât understand or care about him, and there were no other important characters, the novel