‘People saw me differently in comedy; I found they misinterpreted my shyness as coldness and my almost constant overwhelming anxiety as anger.’

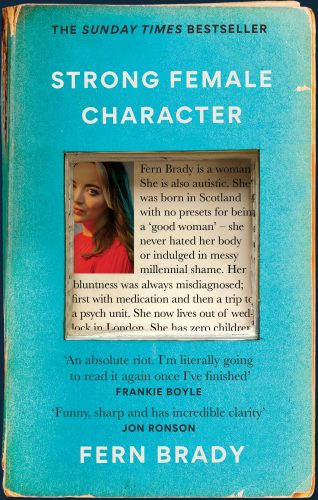

Fern Brady, comedian and Taskmaster alumni, struggled with her mental health for years before accepting that she was autistic and might need people around her – including herself – to make certain adjustments to their expectations. This memoir recalls some of her key experiences growing up autistic and looks at the missed opportunities there were to help her.

What’s it about?

See above. Fed up with most people’s understanding of autism being limited / full of misunderstanding, (perhaps because what limited understanding there is is typically gathered from what Brady calls ‘autistic adjacent’ people, rather than from autistic people themselves, or focused on ideas gathered from historical studies of autistic boys) Brady set out to establish her reality as an autistic woman, describing her past and present experiences with the new insights that her acceptance of her diagnosis has granted her.

For instance, while recounting an old family story about how she acted like a devil child at a family wedding ‘for no reason‘ (my italics), then refused to pose for photos after being fed Chewits to calm her down, Brady recalls in detail the sensory overload induced by the uncomfortable dress and tight hairstyle, and notes wryly that, ‘no one who was just experienced a meltdown is [likely to be] up for doing a photoshoot, with or without Chewits.’ This self-awareness is essential, since Brady spent her childhood being told she was evil by her family and weird by her ‘friends’ and still struggles with regular meltdowns that, without understanding from herself and those closest to her, would doubtless feel even more debilitating.

What’s it like?

Matter-of-fact and often deeply sad, this could read as primarily a tragic collection of moments-when-people-or-life-was-horrible-to-Brady, but for the humour intrinsic in her writing: ‘Prozac didn’t stop me accidentally insulting people in everyday conversations; it just lent a zen-like calm to my delivery.’

Still, be prepared for trauma: from a young Fern contemplating suicide, to a teenager Fern being ‘educated’ in a mental institution, to young adult Fern being assaulted by a partner, there’s a wealth of unpleasant incidents within these pages.

Despite this, Fern’s style keeps the narrative from feeling overwhelmingly ‘heavy’, in part because so many of her recollections trigger disbelief on her part that she wasn’t diagnosed earlier. When her mum casually recollects that Fern was always ‘clawing at herself’, or when Fern discusses the sheer randomness of her very specific special interests (interpreted by her family and teachers as simply being ‘studious’), I could feel vividly her sheer astonishment and frustration that no one took the time and trouble to investigate the cause of her difficulties. Bitterly, she notes of one child, ‘[his] equally clever brother went on to be diagnosed autistic by the time we started high school, in case anyone thinks no one was getting diagnosed back then’.

Most frustratingly, teenage Brady suggests to a psychiatrist that she thinks she might have Asperger’s Syndrome (an older term for a particular subtype of autism), only to be laughed at and patronisingly assured that she couldn’t possibly be autistic because she could make eye contact and had a boyfriend – despite her finding her family environment so noisy and overwhelming that she was spending hours in the evenings simply rocking in a chair or repeatedly punching walls in an attempt to regulate her emotions.

Final thoughts

This was a fascinating and saddening insight into the difficulties experienced by an autistic woman and the chaos that trying to cope with life without recognising or making allowances for autism can cause. There is a lot of discussion about the social expectations of women and how being an autistic woman subverts these, partly because of the lack of ability to read social cues and therefore recognise the expectations, and partly because autistic people are far less likely to embrace a ‘herd mentality’ and more likely to pursue their own desires, including sexual desires.

I find it interesting that Brady has said elsewhere that she wonders whether being diagnosed earlier would actually have held her back in life, because her parents would have been even more over-protective than they were and because (instead of expecting her to achieve because she was clever) she might have been perceived by teachers and employers as less capable (because autism still carries a lot of stigma in relation to expectations around intellectual capability and achievement). Possibly, receiving a diagnosis at a much younger age could have even exacerbated Brady’s struggles: when first diagnosed she seems to hate the idea of ‘looking’ autistic, revealing that she has imbibed many of the negative stereotypes of autistic behaviour, and this could easily have been even more difficult as a teenager growing up in a time and place where far fewer supportive resources existed than do today.

Personally, I can’t help wishing that young Brady had found help much, much sooner, and hoping that her book will help other young women recognise and begin to come to terms with their neurological divergence in the same way that reading ‘Aspergirls’ by Rudy Simone began to do for Brady.

Recommended as a fascinating memoir for its own sake and also as an excellent gift for anyone who still maintains that ‘we’re all on the [autistic] spectrum somewhere’* or ‘we’re all a little bit autistic’**.

‘Strong Female Character’,

Fern Brady,

2024, Hachette, paperback

* No. Just, no. It’s not that kind of spectrum.

** Nope. Anyone may have a trait that’s commonly seen in autistic people, though, because autistic people are human and autistic traits are human traits, albeit often experienced at a higher dose.