Why are women still left holding the baby?

Today girls often outperform boys in education and grow up to become women who have successful, absorbing and well-paid careers. They may even earn more than their partners, with whom they typically have equal and rewarding relationships. And then many women have children, and find themselves back in the 1950s, proving that today’s so-called equality is nothing more than a myth propagated by a relentlessly sexist society.

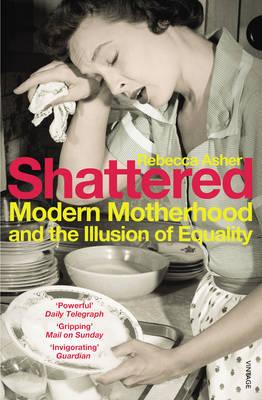

This, at least, is Rebecca Asher’s argument in ‘Shattered: Modern Motherhood and the Illusion of Equality’.

What’s it about?

Er, see above. To find the answer, Asher picks apart UK attitudes and policy, from mother-centred maternity care to maternity and paternity leave through to the role played by advertising, the media and the realities of flexible working. Suitably appalled by all the above, she turns her attention to the ways other countries approach these issues and suggests a raft of measures the UK government needs to take if its stated desire to support ‘shared parenting’ is to ever be more than a meaningless slogan.

What’s it like?

Utterly convincing. Asher uses a mixture of research and anecdotes from a wide range of mothers and fathers to build up a picture of parents as a group systematically guided by the state into particular moulds. Although I was initially unconvinced by her insistence that fathers should have paid time off work to attend antenatal appointments, there is sound logic behind her conviction, (failure to involve fathers-to-be at this stage does reinforce the notion that babies are a woman’s business,) and it is concerning that many NHS trusts actually discourage fathers’ attendance in case they are domestic abusers.

Asher uses a mixture of research and anecdotes from a wide range of mothers and fathers to build up a picture of parents as a group systematically guided by the state into particular moulds.

Similarly, although my instinctive response to her insistence that hospitals need to provide space for fathers to stay overnight with new mothers was to raise a dubious eyebrow – and who will fund that, my dear? – a little reflection found me recognising the value of her argument. Fathers leave at curfew, even if mothers have endured days of labour followed by a caesarean and are catheterised and drugged up to their eyeballs. Such mothers can feel helpless, while those who have experienced easier births become experts in nappy changing and feeding, ready to slip into the role of guide when the less-experienced father returns in the morning. (“No, dear, not like that, like this.”)

Asher discusses typical parenting scenarios to explore the underlying cultural assumptions. For instance, Mothers and fathers typically work out whether or not it is “worth” the mother going back to work by deducting childcare costs from her wages alone. This seems entirely logical, but the assumptions behind it are insidious: the child is the property of the mother; the mother needs to organise the care for the child as she is the one absenting herself from the core parenting role. For fathers, parenting is seen as almost a bolt-on to their other commitments, something to be attended to between Real (paid) Work and precious leisure time.

Asher discusses typical parenting scenarios to explore the underlying cultural assumptions.

This isn’t simply a feminist polemic. Asher is equally concerned about men’s experiences, although she recognises that they are not always reluctant to be left-out of caring for their children. She argues that current practices create a “sense of male entitlement, [which] together with the knowledge that women will always be there to carry on parenting when they just don’t fancy it, means that men have a license to keep their distance.” This chimes perfectly with my own feelings and the experiences of other mothers I know: women are the default parent, even if they have returned to work full-time.

This isn’t merely a complaint either. Asher offers (costly) solutions and envisages a genuinely equal society in which men and women rear children equally and both work flexibly in order to accommodate this. It isn’t quite the pipe dream it sounds, as other countries are already doing some of this, and of course, ultimately, two incomes commensurate with the employees’ abilities will bring in more money to government coffers than one.

Sounds like a utopia. But does it work?

I have some concerns, which I’ve discussed in a separate post. In the meantime, I’d love to hear your thoughts on shared parenting. Is it essential for genuine equality, impossible to achieve, or even an undesirable diversion from ‘the real issues’?