I LOVE Jane Austenâs works, so when I saw this book of Austen focused essays in a local charity shop I knew I wasnât leaving without it.

Pretending to my husband that this was a vital teaching resource, I dashed to the til and nearly skipped out the shop.

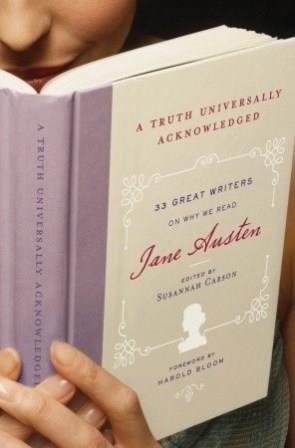

Interestingly, my copy hails from America and the subtitle and cover image are different from the UK edition. The American version seems determined to stress the academic nature of the book so the subtitle states that the book contains â33 great writers on why we read Jane Austenâ and the cover features a hint of a smiling reader holding a copy of what purports to be this book. The overall impression is elegant and tasteful. When I contrast this to the British version I am rather pleased to have my âspecial editionâ. I find the subtitle more sensational and less accurate (â33 reasons why we canât stop reading Jane Austenâ) and the scattered pictures of various colourfully depicted readers reminded me of the front cover of a childâs book of nursery tales.

The idea

Carson has gathered together 33 short pieces of writing on Austen and her works, purportedly in order to explore why so many people still read and enjoy Austen today. Some of these are critical essays, most are taken from introductions to editions of the stories but there is a great diversity of forms, including letters and even one recorded conversation. There are a range of voices, from modern writers to Austenâs contemporary critics, and a range of approaches, ranging from the biographical to the purely exclamatory.

The approach

I liked the idea of a range of writers and approaches but I was soon struck by the lack of clarity. The contents pages list the articles included, but there is no attempt to place them in any kind of context. I have generally found that, when reading non-fiction, it is helpful to be aware of the context of a piece of writing. Carson offers no help here at all. I had to search through the permissions and acknowledgements page at the back of the book to confirm that some of the essays had originally been prefaces. The pieces are evidently not organised chronologically (though again, this is only clear from my knowledge of the contributors and reading the sketchy contributor biographies at the back of the book). I thought this was a shame as a chronological approach could potentially have shown some historical development in approaches to Austen.

However, the sheer eclecticism of the collection means that it is difficult to create a central strand. Carsonâs approach, in so far as it exists, appears to be text based â essays which primarily focus on âPride and Prejudiceâ, for example, are grouped together. This is not necessarily helpful as readers are unlikely to read these essays in the same linear way they might approach a story. I thought that a clearly signalled chronological or thematic approach might have been more helpful to readers.

The supporting materials

There is a brief foreword by Harold Bloom followed by a longer introduction by Carson. I felt the praise in both to be rather excessive, claiming that Austen’s novels “inform our understanding of what it is to be human” among other magical qualities she apparently possessed. I admire Austen as a writer but I dislike the elevation of any writer to a mythical status and Bloomâs sweeping claim that âthose who now read Austen âpoliticallyâ are not reading her at allâ annoyed me with its implication that there are right and wrong positions to take regarding any writer. I have never been impressed by the notion that not everyone can âtruly understandâ a writerâs particular genius. Instead, I am a strong believer in allowing everyone to reach their own (well reasoned and logically supported) positions in relation to texts and their authors. This is, however, a minor complaint in relation to these materials.

After establishing her own perspective, Carson briefly sketches each essayist’s central position. I didn’t find the order of this to be helpful. The links the editor makes are relevant, but I would have much preferred a chronological approach â if indeed such a summary is necessary at all. It is really a rather dull approach and a shame the editor didn’t focus in on one or two key articles and her own response, but I believe that this is simply the way in which introductions to collections of essays generally work. I would not bother reading either the introduction or the foreword again but they do succeed in suggesting the multiplicity of approaches to Austen.

As I already noted previously, I thought it was disappointing that the essays were not helpfully contextualised. It would have been simple enough to write a brief paragraph above each essay noting who the author was and why the piece was written. The rather brief author biographies in the back of the book are alphabetical rather than following the structure of the essays in the book, which I found mildly irritating, and there was generally on clue regarding the context. E M Forster appears to be writing a foreword for a collected works â specifically the 1923 Oxford edition edited by R W Chapman. Surely this would be worth mentioning? One essay is in the form of a dialogue but no account is made of its genesis. I found this lack of information increasingly frustrating and felt that this did reduce my enjoyment of the book.

The 33 pieces

As suits a book with such diverse contributors and approaches, my response to the essays was mixed. I did read them in order, simply because there seemed to be no good reason not to, but there is certainly no requirement to do so and it would be quite fun to dip in and out of these like a box of chocolates. (Again, having more details in the contents page would support this.) I will not discuss all the essays but will instead comment on a selection to give an idea of the quality and variety.

I was very pleased by first essay âWhy We Read Jane Austen: Young Persons in Interesting Situationsâ. Interesting points were made about marriage in the nineteenth century, Austen’s focus on moral character and use of landscape. The second essay, âThe Radiance of Jane Austenâ, by contrast, says nothing useful. It is simply a paean to Austen and I found it a little annoying. I suppose it is useful to give a flavour of the depth of feeling some people will develop for a writer, but my feeling is that if youâve selected a book of essays on Austen, youâre probably either already quite keen on the writer or a diligent student. In neither case would reading gushing prose be helpful or, I would imagine, interesting.

âSix Reasons to Read Jane Austenâ is, unsurprisingly, rather listlike and, again, little more than a homage. Later on, âReading Northanger Abbeyâ is an interesting examination of this slightly less typical novel by Susannah Carson. It is more academic in style than the preceding pieces â unsurprisingly as she is a PHD student. The link she made to Mr and Mrs Bennett confirmed my own thoughts, which is of course always gratifying, and identified a genuine problem at the heart of the novel. The essay gathers pace as Carson inverts her argument â could Austen have deliberately crafted this flaw in order to make a point? It is a worthwhile argument. I enjoyed Ian Wattsâ piece âOn Sense and Sensibilityâ for similar reasons. It is true that I have more of an academic interest than a general reader might, but these are short and accessible pieces which I think a range of readers could find interesting and worthwhile reading.

They’re not all simple hymms to Austen’s greatness

There is a genuine variety of approaches. For instance, Lionel Trilling discusses student response to Austen as a way into establishing a humanist perspective. There was a very interesting point made by John Wiltshire considering why the films of Austen’s novels are problematic. One writer briefly considers how Austen is presented and how this alienates some potential readers and even some critics. I did enjoy the diversity of approaches and thought it was a strength of the book that the contributors came from a range of backgrounds as they could offer different perspectives. One essay that surprised me was Martin Amisâ: it seems out of place as it is forcefully critical of Austen’s ‘Mansfield Park’, and this led me to wonder with renewed force what the organising force behind this collection was. It certainly didnât seem like Amis was writing about âreasons to read Austenâ though I suppose he covers âwhy we read Austenâ.

Inevitably, there is some overlap in terms of quotations used and comments made, but this is a minor feature of the text and did not bother me in the slightest. Occasionally, the writers referred to each others’ essays, which I also found interesting as it helped to develop a sense of overall criticism and response to the novels. There were a few writers who conveyed an irksome sense of âknowing bestâ (Eva Brann states that Austen’s work does not have themes and is resistant to interpretation, which makes me wonder how on earth I manage to teach it!) but generally there was a feeling of discussion and a pleasant sense of sharing ideas.

Overall thoughts

While this collection is certainly not perfect, I did enjoy it and it is something I will definitely reread. (I even found a few ideas to share with my students so it turned out I wasnât fibbing to my husband after all!) I liked the diversity of approaches and thought it would make a great gift for someone who is genuinely interested in Austen.

One significant omission is that there are no noticeable references to Austenâs juvenilia or to her unfinished novel âSanditionâ. I don’t find this omission surprising as Austen is widely known as the author of six competed novels and I didn’t know anything about her other works until I studied her at university; however, I did think it was a missed opportunity to bring these works more widely to the publicâs attention.

All the essays are relatively short and they are all easy to follow and understand (with the exception of Harold Bloomâs essay on Persuasion, which I found rather dense and unrewarding). There is no glossary included as none is required. This is clearly a book aimed to a general reading audience rather than an academic reader.

Despite its flaws, I am very glad I found this and know I will eventually reread many of the essays. I would recommend it to anyone who has a basic familiarity with at least some of Austenâs books and a genuine interest in literature. In particular, I would recommend it to students studying Austen as a gentle introduction to literary criticism.

‘A Truth Universally Acknowledged’,

Susanna Carson (ed.),

2009, Random House (NY), hardback