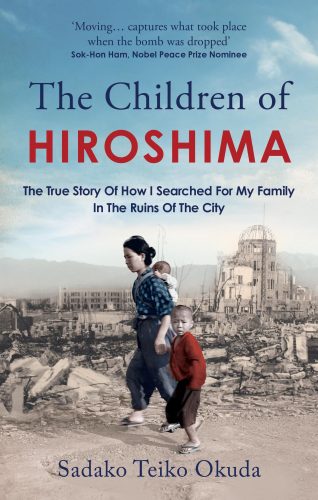

‘I wonder if people realise how many victims of Hiroshima were not adults. but young children’.

In her moving account of searching the ruins of Hiroshima for her niece and nephew, Sadako fills in this gap in our understanding with powerful, horrifying stories of loss, destruction and innocence.

What’s it about?

When the atomic bomb exploded over Hiroshima in 1945, Sadako was living on Osaki-Shimo Island, from which the blast could be felt but not yet understood. As rumours flooded her village of complete devastation in Hiroshima, locals began travelling to the mainland to search for family members. This is Sadako’s account of her eight days of searching for her niece and nephew in and around ground zero.

Based on diary entries made at the time and published in Japan in 1979 and Korea in 1983, Sadako’s words have taken longer to reach the English speaking world, being published in the U.S.A in 2008 as ‘A Dimly Burning Wick’ and, finally, in 2025 in the U.K. as ‘The Children of Hiroshima’. (Presumably the title change has arisen at least partly as a recognition of the less religious nature of readers as a whole in the U.K.)

What’s it like?

Devastating. Powerful. Purposeful. Sadako writes simply of her efforts to find her niece and nephew, recounting the meetings she had with children and adults she met as she ventured out each day into a world that was both burning and dying, in which she found despair and faith in people whose wounds were such that they frequently died during her time with them.

Although the people Sadako meets and seeks to help are fatally injured, their injuries are described simply and, though horrific, are not gory or gruesome. Shocking, yes, for such is the horrific impact of the bomb, but not recorded in a way that would make most feel unable to read their stories.

Essentially, the main memoir is organised both chronologically and by who Sadako interacted with. As she continues to seek her family, she meets orphans and siblings and each brief chapter focuses on her experiences with a few of the victims. This is the core of the book, supported by various forewords and appendices that briefly clarify and contextualise the contents within Sadako’s own life and the broader social and psychological impacts of the atom bomb.

Hope in the ruins

Obviously, a non-fiction account of a deeply traumatic and devastating event will be sad, but ‘The Children of Hiroshima’ transcends simple sadness by allowing for wonder. Despite everything, despite the terrible circumstances, most people, especially the children, are focused on maintaining social bonds and caring for others. Perhaps this is why Sok-Hon Ham, nicknamed “the Gandhi of Korea” wrote in his foreword to the Korean edition that this book gave him, ‘a vision of a small space between the deeply piled decaying corpses where a trembling new green leafy shoot emerged’.

Final thoughts

This is a powerful call for all people to come alive to the brutal horror of atomic war (two of the chapters have been published in Japan as children’s books, which surprised me as they are, of course, very sad). At one point Sadako, writing a letter to her mother, asks: ‘Mother, how can such a thing be allowed to happen?’ In her afterword she is even more explicit, stating that ‘I want to teach the youth of today…that nothing is more important than unity and peace and that there is never a justification for such cruelty.’ Finally, she urges that, ‘I hope that you will take up the cause I have carried and make it your own’.

Read this to understand how the spirit of humanity can survive even as human beings are brutally exterminated en masse, then read it again to reinforce your conviction that the horror visited on Hiroshima – and on Nagasaki – must never be allowed to happen again.

‘The Children of Hiroshima’,

Sadako Teiko Okuda,

2025, Monoray, paperback

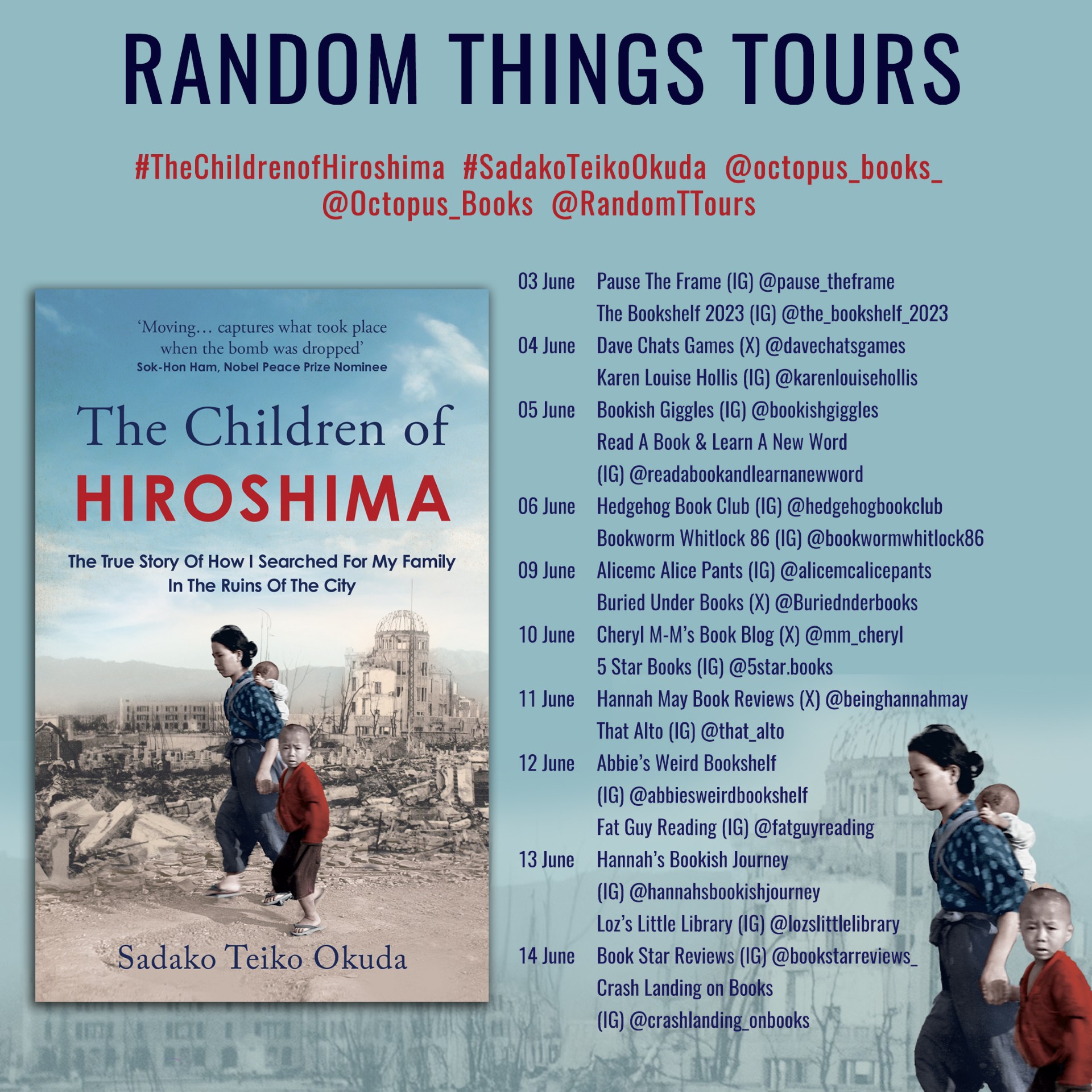

Many thanks to the publisher and Anne Cater’s Random Things Tours for providing me with a copy of this book in exchange for an honest review and a spot on the blog tour.

Want to know more? Follow the tour:

1 Comment

Thanks for the blog tour support x