What would life be like if your brother communicated with you through the wind, the waves, the movement of a fox? What would life be like if he communicated with you despite being dead?

Meet 19 year old Matthew Homes. He’ll tell you he doesn’t hear voices. But he does hear his brother. ‘I’ll tell you what happened because it’ll be a good way to introduce my brother. His name’s Simon. I think you’re going to like him. I really do. But in a couple of pages he’ll be dead. And he was never the same after that.’

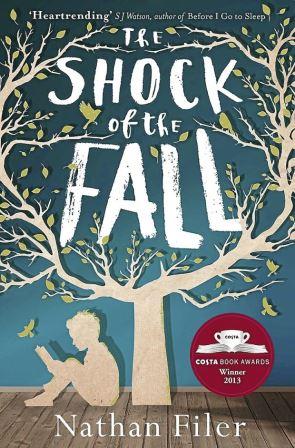

‘The Shock of the Fall’ is an accomplished debut novel from Nathan Filer, creative writing MA holder, performance poet and former mental health nurse.

What’s it about?

A young boy growing up into a young man while dealing with the early death of his brother and struggling with mental illness that leads to him being institutionalised. It’s about grief and loss and coping and how life is often bitterly cyclical.

What’s it like?

Very interesting. My synopsis risks making the book sound grim, but it isn’t. Matthew Homes, the book’s narrator, is matter-of-fact and occasionally angry, but the story is constructed in such a way that the reader is perpetually interested and intrigued.

Filer aimed to create suspense throughout and he achieves this by revealing the fact of Simon’s death on page two but only gradually unveiling how he died and Matthew’s involvement. (Some reviewers have suggested readers are also meant to be ignorant of the name of Matthew’s illness until the end of the novel; I disagree as I think the symptoms – and therefore the nature of his disease – are clear throughout.)

‘The Shock of the Fall’ has been compared to Mark Haddon’s ‘The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time’ and I can see why: both approach difficult life events through a first person narrator with an unusual perspective. Both have an ‘offbeat’ narrative voice and make use of physical elements as well as verbal ones to tell their story. (‘The Shock of the Fall’ incorporates official letters and different fonts to help create a sense of time and place.) I think the comparison is well-justified and found both novels well worth reading.

It’s easy to read but powerful, too, offering an insight into living with schizophrenia.

It’s easy to read but powerful, too, offering an insight into living with schizophrenia, especially the cyclical nature of the disease. (Although it’s perhaps worth noting that, when interviewed, Filer has refused to label Matthew’s particular brand of mental ill-health.) Matthew’s account of his time in an institution – “there is nothing to do. nothing” – and the efforts of his mental health team to support him make for very sad reading but the kind of sad that makes you want to do something rather than the kind of sad that just depresses you.

Inevitably Matthew is not always the most easy to follow or reliable of narrators. The focus of the novel switches from past to present and back again repeatedly as Matthew types up the story of his life to date, interrupted by care workers reading over his shoulder and the requirements of his care plan. At one point he offers three versions of a key conversation and it is never clear which happened – though perhaps this is the point. No matter what stories we tell ourselves about the how or the why of things, the heart of certain happenings is unchangeable. It’s a testament to Filer’s skill that the reader never feels lost or confused, and it helps that there is a clear narrative movement towards a kind of resolution, even if it is, by necessity, an incomplete one. In fact, Matthew chooses where to stop his story, and it’s quite beautifully done.

Final thoughts

This novel has had a lot of hype and won the Costa Book Award’s ‘First Novel Award’ in 2013. I think having my expectations set so high actually meant I didn’t quite enjoy it as much as I could have done but I did find it genuinely interesting, especially the way Matthew frequently meditates on the fallible nature of his memories.

The honesty of Filer’s portrayal of Matthew – or Matthew’s portrayal of himself – means he is not always likeable, though the reader is likely to feel tremendous sympathy for him. In fact, his first words to the reader tell us that ‘I am not a nice person’, but the innocence of his first recollection highlights that his ‘not-niceness’ is that of a typical human being rather than a genuinely unpleasant individual.

The narrative focus is on how Matthew experiences his illness and the effects this has on him and his family.

I liked the way Filer avoids putting Matthew’s illness in a box; Matthew himself doesn’t speculate over the origins of his illness (though he refers in passing to what seems to be quite heavy cannabis use and a family history of vulnerable mental health). Instead, the narrative focus is on how Matthew experiences his illness and the effects this has on him and his family.

Similarly, I appreciated that, although one could criticise certain aspects of the mental health service as it is presented in the book, Matthew’s own experiences are presented as personal rather than political. I feel this makes him a realistic character.

I may reread this in future and I will keep an eye out for future offerings by Nathan Filer – if there are any. When interviewed he has been reluctant to commit himself to the idea of writing a second novel, suggesting that “there’s a degree of expectation [to write another novel]. But really, that expectation belongs to other people. IÂ don’t actually have to.” If he feels he only has the one book in him, fair play – it was well worth writing.

Recommended.