This is why I love book groups: they draw your attention to books you might otherwise never have discovered.

What’s it about?

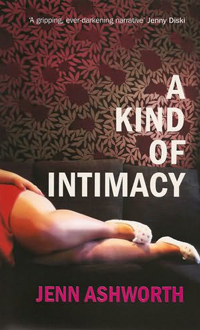

Jenn Ashworth’s debut novel, ‘A kind of Intimacy’, stars Annie, a lonely, obese woman who narrates her increasingly awkward attempts to build a new life and get to know her new neighbours – without revealing too much about her past.

I found the blurb intriguing and the opening lines drew me in:

“After the van had been loaded and sent on its way I took off all my clothes and kicked the sofa I was about to abandon. Not just a little kick either. I really belted it.”

Annie isn’t just abandoning a sofa. Gradually, through her recollection of the past and her inadvertent admissions to her neighbours, she reveals a darkly disturbing history and, more frighteningly, a deeply deluded sense of her self and her interactions with the world. From her early attempts to seduce the milkman to her unjustifiable conviction that next-door neighbour Neil is preparing to leave his sexy young girlfriend, Lucy, for her, Annie reads the world around her as she wishes it was, twisting evidence in ways that are occasionally astonishing. (Noisy sex next door? It must be Neil’s way of letting Lucy down gently.)

What’s it like?

Noisy sex next door? It must be Neil’s way of letting Lucy down gently.

The gaps between Annie’s narrative and the reality the reader can perceive initially create sympathy, especially as the other characters can be distinctly unsympathetic – Lucy is cruel about Annie’s weight, neighbourhood watch member Sangita is a gossip – but as time draws on, Annie’s misinterpretation takes a darker turn and her deliberate obtuseness becomes horrifying.

It might sound odd to say that I enjoyed this, and perhaps I mostly mean that I enjoy thinking over the whole conceit in retrospect. While reading, I wondered how far Annie really was self-aware and conscious of the narrative she was spinning; by the end of the novel it seemed unbelievable that she could really believe what she was saying. That isn’t to say that I thought the book was flawed. Actually, the ending is so effective because all the preceding events help the reader to understand that Annie’s insistent lack of awareness is not pathetic or sad but dangerous.

Annie has “too much in common with the rest of us to be written off as a monster”

Unusually, I felt the praise on the back cover was entirely justified. Alison Flood from The Guardian notes that ‘A kind of intimacy’ has been compared to ‘Notes on a Scandal‘ by Zoë Heller, which is entirely appropriate (and another book I absolutely loved). The blurb suggests that Annie has “too much in common with the rest of us to be written off as a monster” and I suspect this is what makes both books so powerful. It is easy to build small interactions into intensely significant ones if you are feeling particularly vulnerable for whatever reason. It is more difficult to be bothered to eat well if you’re persistently cooking – or, eventually, microwaving – for one. These small truths make us feel that we can understand some of Annie’s world, that she is not an Evil Monster, but an ordinary person gone badly awry.

Annie’s narrative voice is very engaging and easy to read; despite being chronically short of time I finished the book within a few days because it was so easy to pick up and slip back into her world. The ending is dramatic, perhaps overly so for some readers, but I felt that it worked well with the preceding material and I liked that there was a definite closure to the novel.

Final thoughts

I really enjoyed Ashworth’s debut novel and will be keeping an eye out for ‘Cold Light‘, her second novel, which has an almost equally intriguing premise. Reading this has also made me want to re-read ‘Notes on a Scandal’, though this will have to wait until I have made a respectable indentation in the ‘borrowed’ section of my TBR pile.

Some readers have complained that Annie’s malaise is too obvious, seen too quickly, and removes doubt from the reader’s mind. I disagree that it should be hidden; by introducing Annie’s deluded perspective early on the reader isn’t wondering whether or not she can be trusted, instead they are wondering with increasing urgency what she has done (does she have a daughter? If so, where is she?) and what she might do yet. This creates a great deal more tension than simply wondering whether or not Annie can be trusted.

Ashworth has been commended for her comic gifts and there is dark humour here, but it’s more shake-your-head-in-mildly-amused-disbelief than ooh-that’s-funny-but-a-bit-naughty-so-I-shouldn’t-laugh-at-it-really. Amusing, but not laugh-out-loud funny. This isn’t intended as a criticism, simply an observation that I would market his book based on its narrative strength and dark tone rather than its comic aspect. (Besides which, I always find this kind of “comedy” deeply uncomfortable as you are being encouraged to laugh at someone who is clearly Not Quite Right.)

In short, I highly recommended ‘A kind of Intimacy’ if you enjoy reading unreliable narrators, novels which focus on personal relationships and / or darkly comic stories.